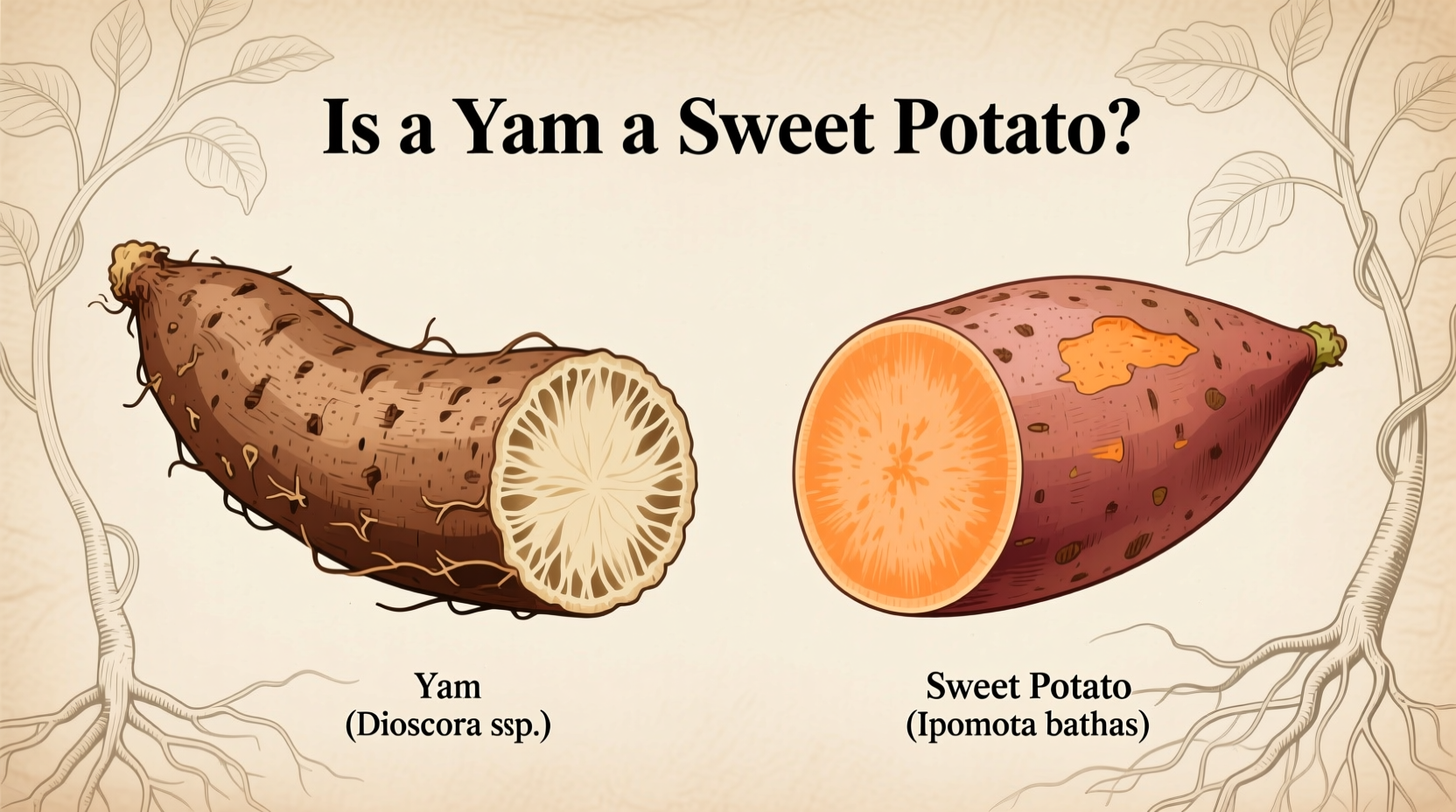

No, a yam is not a sweet potato—they're completely different plants with distinct origins, characteristics, and culinary uses. True yams (Dioscorea species) originate from Africa and Asia, have rough, bark-like skin, and are starchy with minimal sweetness. What Americans call “yams” are actually orange-fleshed sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas), which are native to the Americas and naturally sweet.

Confused about yams versus sweet potatoes? You're not alone. This common kitchen confusion affects millions of shoppers who grab “yams” at the grocery store, only to discover they've actually selected sweet potatoes. Understanding the real difference matters for both cooking success and cultural accuracy. Let's clear up this decades-old mix-up with science-backed facts you can trust.

The Great Yam-Sweet Potato Mix-Up: Why It Happened

The confusion between yams and sweet potatoes in the United States dates back to the transatlantic slave trade. Enslaved Africans encountered the New World's sweet potatoes and noticed their resemblance to the true yams they knew from West Africa. They began calling them “yams” as a cultural reference. When orange-fleshed sweet potato varieties became commercially popular in the 1930s–1950s, producers adopted “yam” as a marketing term to distinguish them from traditional white-fleshed sweet potatoes.

| Characteristic | True Yam | Sweet Potato (Sold as “Yam” in US) |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Family | Dioscoreaceae | Convolvulaceae (Morning Glory) |

| Origin | West Africa, Asia | Central/South America |

| Skin Texture | Rough, bark-like, blackish-brown | Thin, smooth, reddish-brown to copper |

| Flesh Color | White, purple, or reddish | Orange, white, purple, or yellow |

| Sweetness Level | Starchy, minimal natural sugar | Naturally sweet (especially orange varieties) |

| Availability in US | Rare (specialty/international markets) | Widely available year-round |

How to Spot the Real Difference at Your Grocery Store

When shopping in North America or Europe, what's labeled as “yams” are almost certainly sweet potatoes. True yams remain uncommon outside African, Caribbean, or Asian specialty markets. Here's how to identify them:

- Check the label: The USDA requires labels distinguishing “sweet potatoes” from true yams. If it says “yam,” it's legally required to also say “sweet potato.”

- Examine the skin: True yams have thick, shaggy skin resembling tree bark, often with root hairs. Sweet potatoes have smoother, thinner skin.

- Consider the shape: Yams typically grow much larger (up to 150 pounds!) with cylindrical shapes. Sweet potatoes are smaller with tapered ends.

- Look at the flesh: Orange flesh means you have a sweet potato. True yams have white, purple, or reddish flesh but never orange.

Why the Distinction Matters for Cooking

Using the wrong tuber can dramatically affect your dish's outcome. True yams contain less sugar and more starch than sweet potatoes, making them better suited for savory applications where you want a neutral base. Sweet potatoes—especially orange varieties—caramelize beautifully when roasted and work well in both sweet and savory dishes.

According to agricultural research from the USDA Agricultural Research Service, orange-fleshed sweet potatoes contain up to 10 times more beta-carotene than white-fleshed varieties. This nutritional difference explains why sweet potatoes have become popular in health-conscious cooking, while true yams remain staple foods primarily in tropical regions.

Global Perspectives on Yams and Sweet Potatoes

The terminology confusion is primarily an American phenomenon. In most countries:

- Nigeria—the world's largest yam producer—calls true yams “ji” in Yoruba and distinguishes them clearly from sweet potatoes (“ewura”)

- In Japan, true yams (yamaimo) are served raw grated, while sweet potatoes (satsumaimo) are roasted or steamed

- Caribbean markets sell true yams as “nyami” or “igname” to differentiate from “boniato” (white sweet potato)

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations documents that true yams account for less than 10% of global production compared to sweet potatoes, explaining their limited availability outside tropical growing regions.

Practical Tips for Your Next Shopping Trip

Now that you know the difference, here's how to get exactly what you need:

- For traditional Thanksgiving “yams”: Look for orange-fleshed sweet potatoes labeled as Jewel, Garnet, or Beauregard varieties

- For authentic African or Caribbean recipes: Search for true yams at specialty markets—they're often labeled as “white yam” or “water yam” (Dioscorea alata)

- For maximum nutrition: Choose orange sweet potatoes for vitamin A or purple varieties for antioxidants

- Storage tip: Never refrigerate either tuber—cool, dark pantries maintain optimal texture and flavor

Setting the Record Straight: A Culinary Historian's Perspective

The mislabeling persists due to historical marketing decisions rather than botanical accuracy. As documented in food historian Jessica Harris's research, the term “yam” was deliberately adopted by Louisiana sweet potato growers in the 1930s to distinguish their orange varieties. This marketing strategy succeeded commercially but created lasting confusion that continues to frustrate chefs and food scientists today.

Understanding this distinction honors both the agricultural heritage of African yam cultivation and the indigenous American origins of sweet potatoes. It also empowers you to make informed choices that match your culinary goals—whether you're preparing West African fufu, Southern candied “yams,” or Japanese roasted satsumaimo.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4