Yes, botanically speaking, a tomato is classified as a berry. This surprising fact challenges common kitchen wisdom but aligns with strict botanical definitions that focus on fruit structure rather than culinary usage or taste.

Discover why your favorite salad ingredient shares botanical classification with grapes and bananas, not strawberries. This comprehensive guide explains the scientific reasoning behind tomato classification, debunks common misconceptions, and reveals other surprising "berries" hiding in your kitchen pantry.

The Botanical Definition That Changes Everything

When scientists classify fruits, they examine plant anatomy rather than taste or culinary usage. A true berry, botanically speaking, develops from a single ovary and contains seeds embedded in pulp. This definition surprises many people because it means:

- Tomatoes qualify as berries because they form from a single flower with one ovary and have seeds surrounded by fleshy tissue

- Strawberries aren't true berries (they're aggregate fruits)

- Raspberries and blackberries are also not berries (they're aggregate-accessory fruits)

- Bananas and grapes are true berries, just like tomatoes

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and university botany departments consistently confirm this classification through their plant science research. Cornell University's School of Integrative Plant Science explains that botanical fruit classification depends on development origin rather than common perception.

Why Your Kitchen Wisdom Gets Tomatoes Wrong

The confusion stems from two different classification systems operating in parallel:

| Classification System | Defines Tomato As | Key Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical Science | Berry | Develops from single ovary, fleshy pericarp, multiple seeds |

| Culinary Tradition | Vegetable | Savory flavor profile, used in main dishes rather than desserts |

This dual classification caused a famous legal battle in 1893 when the U.S. Supreme Court case Nix v. Hedden ruled tomatoes should be taxed as vegetables for tariff purposes, despite their botanical classification. The court acknowledged tomatoes are "botanically and scientifically a fruit" but legally treated them as vegetables based on common usage.

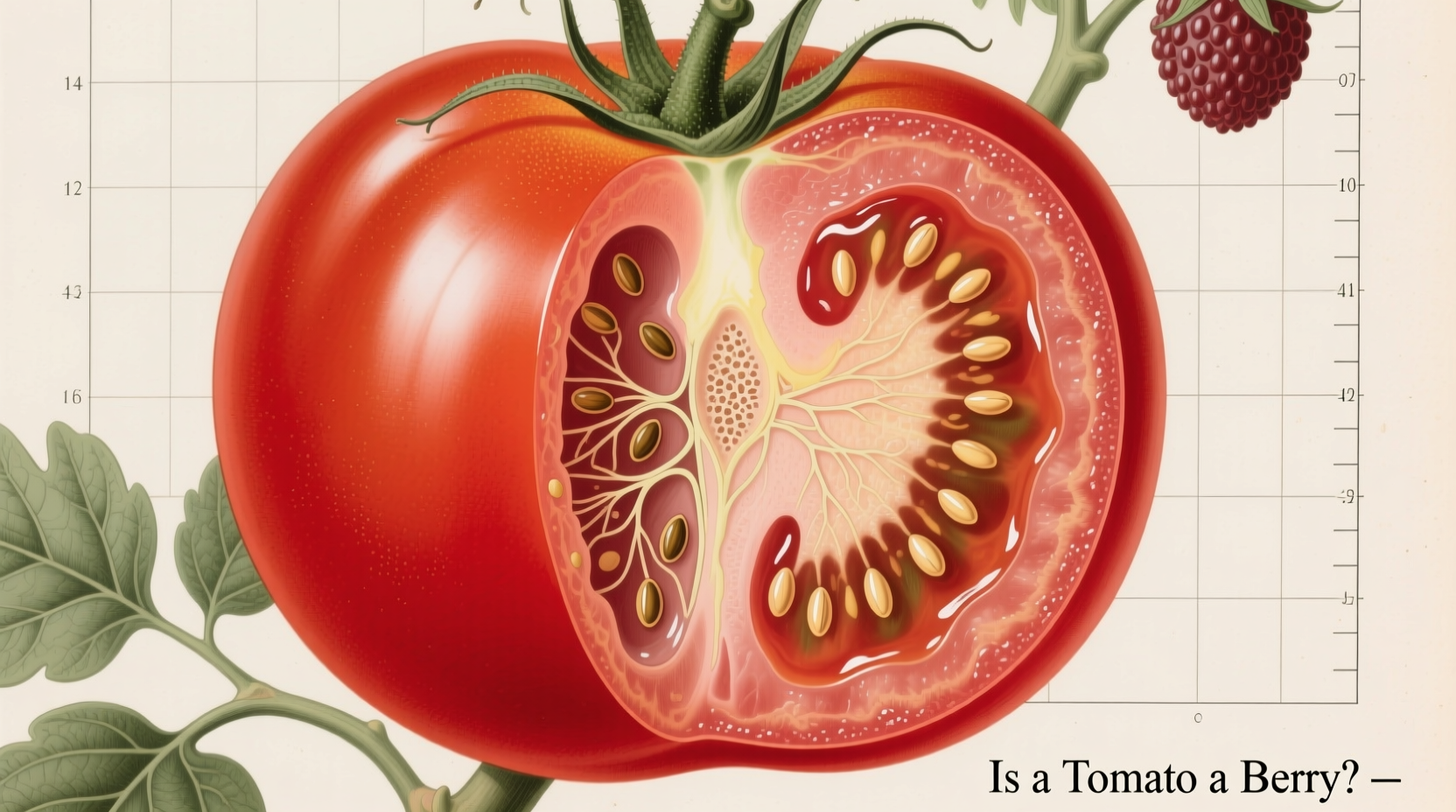

Tomato Anatomy: The Berry Blueprint

Examine a tomato's internal structure and you'll see textbook berry characteristics:

- Pericarp development: The entire fleshy part develops from the ovary wall

- Seed arrangement: Multiple seeds embedded in gelatinous pulp

- Origin: Forms from a single flower with one ovary

Compare this to strawberries, where the "seeds" are actually individual fruits on the outside of the fleshy receptacle. Or raspberries, which consist of multiple drupelets. The tomato's simple structure perfectly matches the botanical definition of a berry.

Other Surprising Kitchen Berries You Didn't Know

Once you understand the botanical definition, you'll discover berries are hiding throughout your kitchen:

- Bananas: Develop from a single ovary with seeds embedded in pulp (though commercial varieties have tiny, undeveloped seeds)

- Grapes: Classic example of true berries with thin skin and juicy interior

- Eggplants: Another nightshade family member classified as berries

- Avocados: Technically single-seeded berries (yes, really!)

- Pumpkins: Belong to a berry subcategory called "pepos"

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew confirms these classifications through their extensive plant taxonomy research, maintaining comprehensive databases of botanical classifications used by scientists worldwide.

When Classification Actually Matters

Understanding botanical classifications isn't just trivia—it has practical implications:

- Gardening success: Knowing tomatoes are berries helps gardeners understand their growth patterns and nutrient needs

- Culinary applications: Berry classification explains why tomatoes work well in both savory dishes and unexpected sweet applications

- Allergy awareness: People with nightshade allergies react to tomatoes' botanical family relationships, not culinary categories

- Preservation techniques: Berry structure affects how tomatoes respond to canning and drying methods

However, for everyday cooking, the culinary classification remains most practical. As noted by food science researchers at the University of California, Davis, "Botanical accuracy rarely trumps culinary functionality in the kitchen." The classification system you use should match your purpose—science for gardening, culinary tradition for cooking.

Botanical Classification Timeline: How We Got Here

The journey to understanding tomato classification spans centuries:

- 1521: Spanish explorers first document tomatoes in Mesoamerica, classifying them as vegetables based on usage

- 1753: Carl Linnaeus establishes modern taxonomy, classifying tomatoes as Solanum lycopersicum

- 1893: U.S. Supreme Court rules tomatoes are vegetables for tariff purposes in Nix v. Hedden

- 1920s: Botanists formally define berry characteristics based on fruit development

- Present: Scientific consensus confirms tomatoes as berries while culinary tradition maintains vegetable classification

Practical Takeaways for Food Enthusiasts

Now that you know tomatoes are berries, how can you apply this knowledge?

- Experiment with tomato-based desserts—they're botanically appropriate!

- Understand why tomatoes pair well with other berries in salads and salsas

- Recognize similar growth patterns between tomatoes and other nightshade berries

- Impress friends with this fascinating food science fact at your next gathering

Remember that both classification systems have validity—the key is understanding which context requires which perspective. Whether you're gardening, cooking, or simply satisfying curiosity, knowing why a tomato is a berry gives you a deeper appreciation for this versatile fruit-vegetable.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4