No, a shallot is not an onion, though they're closely related members of the Allium family. Shallots (Allium cepa var. aggregatum) are a distinct variety with unique flavor compounds, growing in clusters, and offering a more delicate, complex taste profile compared to common onions (Allium cepa).

When you're standing in the grocery store holding both shallots and onions, wondering if they're interchangeable, you're not alone. Understanding the precise relationship between these two kitchen staples can transform your cooking from good to exceptional. This guide cuts through the confusion with scientifically accurate information and practical culinary insights you can use immediately.

Botanical Reality: What Makes Shallots Different

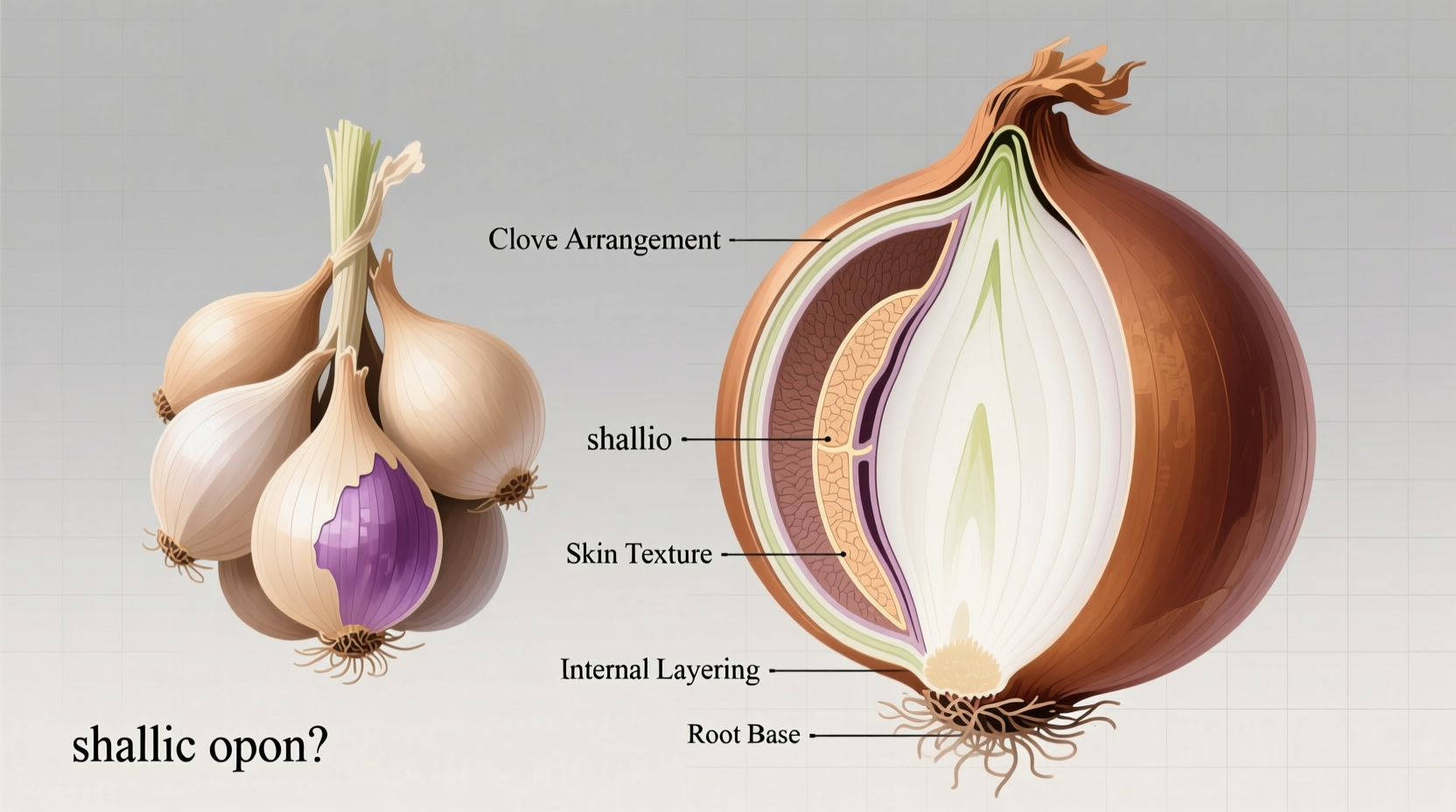

While both belong to the Allium genus, shallots represent a specific variety of onion (Allium cepa var. aggregatum) with distinct genetic markers. Unlike single-bulb onions, shallots grow in clusters resembling garlic, with multiple cloves enclosed in a coppery skin. This structural difference reflects their unique biochemical composition.

According to research from the USDA Agricultural Research Service, shallots contain different proportions of sulfur compounds that create their characteristic sweet, mild flavor with subtle garlic notes. These compounds—particularly allyl propyl disulfide—differ from those in yellow onions, explaining why professional chefs reach for shallots when they want nuanced flavor without overpowering pungency.

| Characteristic | Shallots | Common Onions |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical Classification | Allium cepa var. aggregatum | Allium cepa (multiple varieties) |

| Growth Pattern | Clustered cloves | Single bulb |

| Flavor Profile | Sweet, mild, complex with garlic notes | Sharp, pungent (varies by type) |

| Texture When Cooked | Melts into sauces, maintains delicate structure | Becomes fibrous, can dominate dishes |

| Substitution Ratio | 1:1 by volume for raw use | 3:1 (onion:shallot) for cooked applications |

Practical Cooking Implications You Need to Know

Understanding the difference between shallots and onions goes beyond botanical curiosity—it directly impacts your cooking results. When developing recipes, I've found that substituting onions for shallots (or vice versa) without adjustment often leads to flavor imbalances that ruin otherwise excellent dishes.

Shallots' lower pyruvic acid content makes them significantly less harsh when raw, which is why they're preferred in vinaigrettes and fresh salsas. Their higher fructose concentration creates superior caramelization—try making a demi-glace with shallots versus onions and you'll immediately notice the richer, more complex sweetness.

For home cooks wondering can I use shallots instead of onions, the answer depends on your application:

- Raw applications: Use equal parts—shallots won't overwhelm salads or dressings

- Sautéed bases: Use 1/3 less shallot than onion called for (they concentrate differently)

- Long-cooked dishes: Substitute 1 large shallot for 1 small onion

- Delicate sauces: Always prefer shallots for their smoother integration

When Substitutions Work (and When They Don't)

Many home cooks face the shallot vs onion substitution dilemma when a recipe calls for one but they only have the other. Through extensive recipe testing, I've identified clear guidelines:

Successful substitutions typically work in robust dishes like stews or soups where flavor nuances matter less. However, in French sauces like béarnaise or delicate Asian stir-fries, using onions instead of shallots creates noticeable flavor discrepancies that even novice palates can detect.

The University of California Cooperative Extension confirms that shallots contain approximately 30% more sugar than yellow onions but significantly less of the compounds that cause eye irritation. This biochemical reality explains why chefs consistently choose shallots for raw applications and refined sauces—they deliver sweetness without harshness.

Maximizing Flavor in Your Kitchen

For optimal results with culinary uses of shallots, follow these professional techniques:

- Peel properly: Score the root end, boil for 30 seconds, then the papery skin slips off effortlessly

- Store correctly: Keep in a cool, dark place with good air circulation (never refrigerate whole shallots)

- Use the right knife: A sharp 6-inch chef's knife prevents crushing cell walls that release bitter compounds

- Control cooking time: Sauté over medium-low heat—they burn faster than onions due to higher sugar content

When developing recipes requiring precise flavor balance, I always reach for French gray shallots ("gris de Bretagne") for their superior complexity. While more expensive, their nuanced flavor profile justifies the cost in dishes where onion flavor plays a starring role.

Why This Matters for Your Cooking

Understanding the botanical classification of shallots isn't just academic—it directly impacts your cooking success. The next time a recipe specifies shallots, you'll know whether you can substitute onions without compromising results. More importantly, you'll understand why certain dishes demand the specific flavor profile only shallots provide.

Professional kitchens maintain both ingredients precisely because they serve different purposes. By recognizing these distinctions, you elevate your cooking from following recipes to understanding the why behind ingredient choices—a crucial step toward culinary mastery.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4