Ever wondered why your kitchen categorizes potatoes with vegetables while tomatoes sit in the "fruit" basket at the grocery store? You're not alone. The question is a potato fruit sparks confusion for home cooks and gardening enthusiasts alike. Understanding this distinction isn't just academic—it affects how you store, cook, and even grow this staple crop. Let's clear up the mystery once and for all with science-backed clarity.

Why Potatoes Don't Qualify as Fruits: The Botanical Breakdown

At the heart of the is potato a fruit debate lies a fundamental botanical misunderstanding. True fruits develop from the ovary of a flowering plant and contain seeds. Apples, tomatoes, and cucumbers all follow this pattern—when you slice them open, you'll find seeds inside.

Potatoes tell a different story. What we eat is actually a tuber—a swollen underground stem that stores nutrients for the plant. Unlike fruits, potatoes:

- Form from modified stems called stolons

- Contain no seeds in the edible portion

- Develop below ground rather than from flowers

- Reproduce through "eyes" (dormant buds) instead of seeds

| Plant Part | Definition | Example | Seeds Present? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | Mature ovary of flowering plant | Tomato, pepper, eggplant | Yes |

| Tuber | Swollen underground stem | Potato, yam | No |

| Root | Underground nutrient absorber | Carrot, beet | No |

The Potato's True Identity: More Than Just a "Vegetable"

While we call potatoes vegetables in cooking, that's actually a culinary term, not a botanical one. In scientific classification, potatoes belong to the Solanum tuberosum species within the nightshade family (Solanaceae)—the same family as tomatoes and peppers, which are botanically fruits.

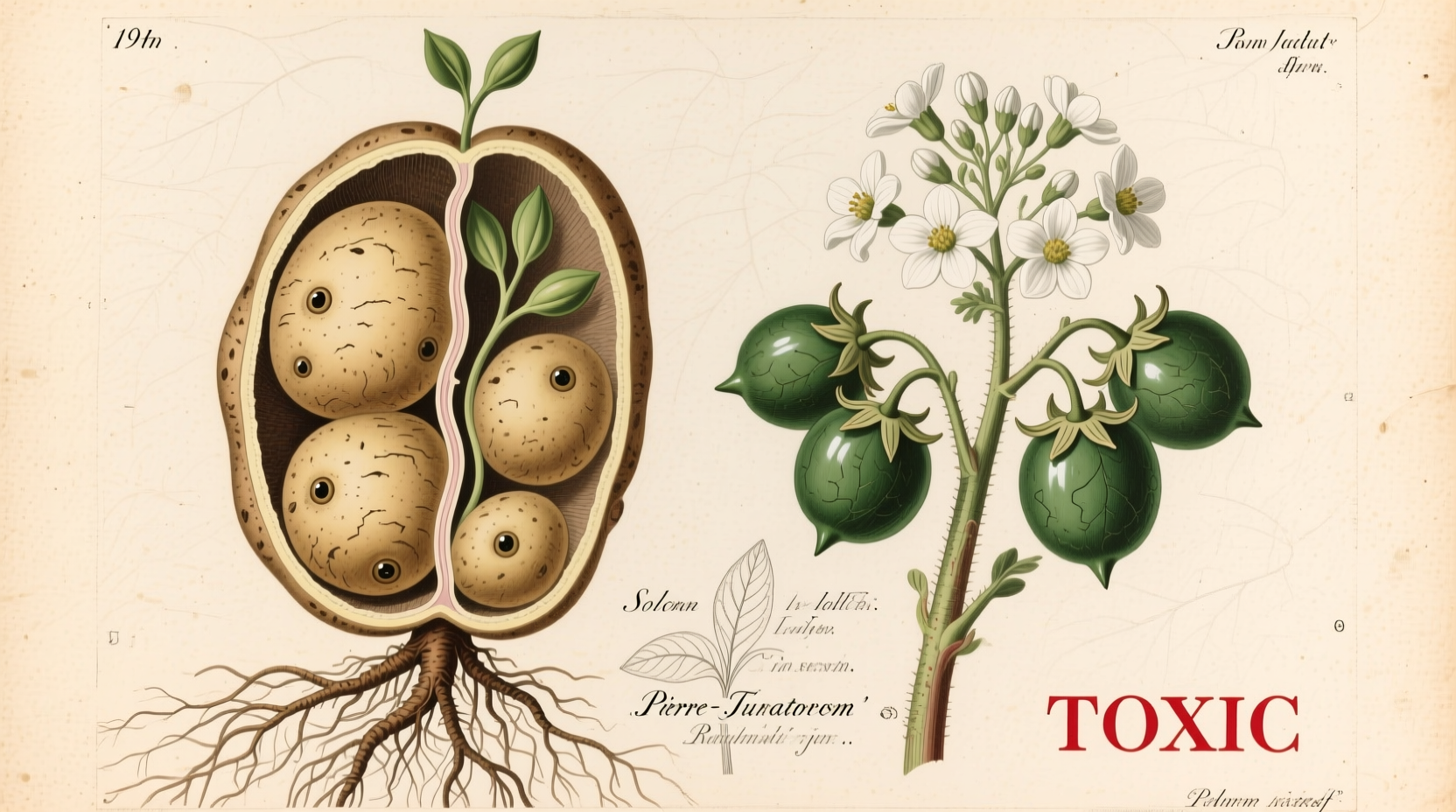

This explains much of the confusion around is a potato fruit. The potato plant does produce fruits—small green berries that contain seeds—but these are toxic and never consumed. The edible part we harvest is strictly the tuber.

Why This Classification Matters in Real Life

Understanding whether potato is fruit or vegetable isn't just trivia—it has practical implications:

Storage Differences

Fruits often ripen after harvest (like bananas), while tubers like potatoes should be stored in cool, dark places to prevent sprouting. Refrigeration actually damages potato texture by converting starches to sugars.

Culinary Applications

Knowing potatoes are tubers explains why they behave differently in cooking than fruits. They provide complex carbohydrates rather than simple sugars, making them ideal for savory dishes rather than desserts (with notable exceptions like sweet potato pie).

Gardening Implications

When growing potatoes, you're cultivating stems, not harvesting fruits. This affects planting depth, hilling techniques, and crop rotation practices to prevent soil-borne diseases—a crucial distinction for home gardeners.

Common Misconceptions Explained

"But tomatoes are fruits, so why aren't potatoes?"

Tomatoes develop from flower ovaries and contain seeds—meeting the botanical fruit definition. Potatoes form as energy-storage stems with no seed production in the edible portion.

"What about sweet potatoes?"

Sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) are actually roots (storage roots), not tubers like regular potatoes. Both are vegetables botanically, but they belong to completely different plant families.

"Why do some people think potatoes are fruits?"

This confusion often stems from seeing the potato plant's toxic fruit berries and misunderstanding their relationship to the edible tuber. Culinary categorization ("vegetables" vs "fruits") further muddies the waters.

Scientific Consensus from Authoritative Sources

The USDA Agricultural Research Service confirms potatoes as tubers in their official plant database, noting their classification as modified stems. Botanists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew explain in their plant profile that while the potato plant produces true fruits (berries), the tuber represents a completely different plant structure.

This distinction appears consistently across botanical literature, including the widely referenced Plant Systematics textbook by Simpson (Oxford University Press), which categorizes tubers as specialized stem structures separate from fruit-bearing mechanisms.

Practical Takeaways for Cooks and Gardeners

Now that we've settled the is potato a fruit question, here's how to apply this knowledge:

- When cooking: Treat potatoes as starch vegetables—they pair better with herbs than sweeteners

- When storing: Keep in ventilated containers away from onions (which accelerate sprouting)

- When gardening: Rotate crops annually to prevent soil depletion and disease buildup

- When shopping: Look for firm tubers without green spots (indicating solanine development)

Understanding the botanical reality behind is potato a fruit or vegetable empowers you to make better decisions in the kitchen and garden. This knowledge bridges the gap between scientific classification and everyday culinary practice—proving that even humble spuds have fascinating botanical stories to tell.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4