The Botanical Truth: Why Potatoes Aren't Fruits

When examining is a potato a fruit, we must start with precise botanical definitions. In plant biology, a fruit develops from the ovary of a flowering plant and contains seeds. Apples, oranges, and tomatoes all fit this definition—they form after pollination and house seeds within their structure.

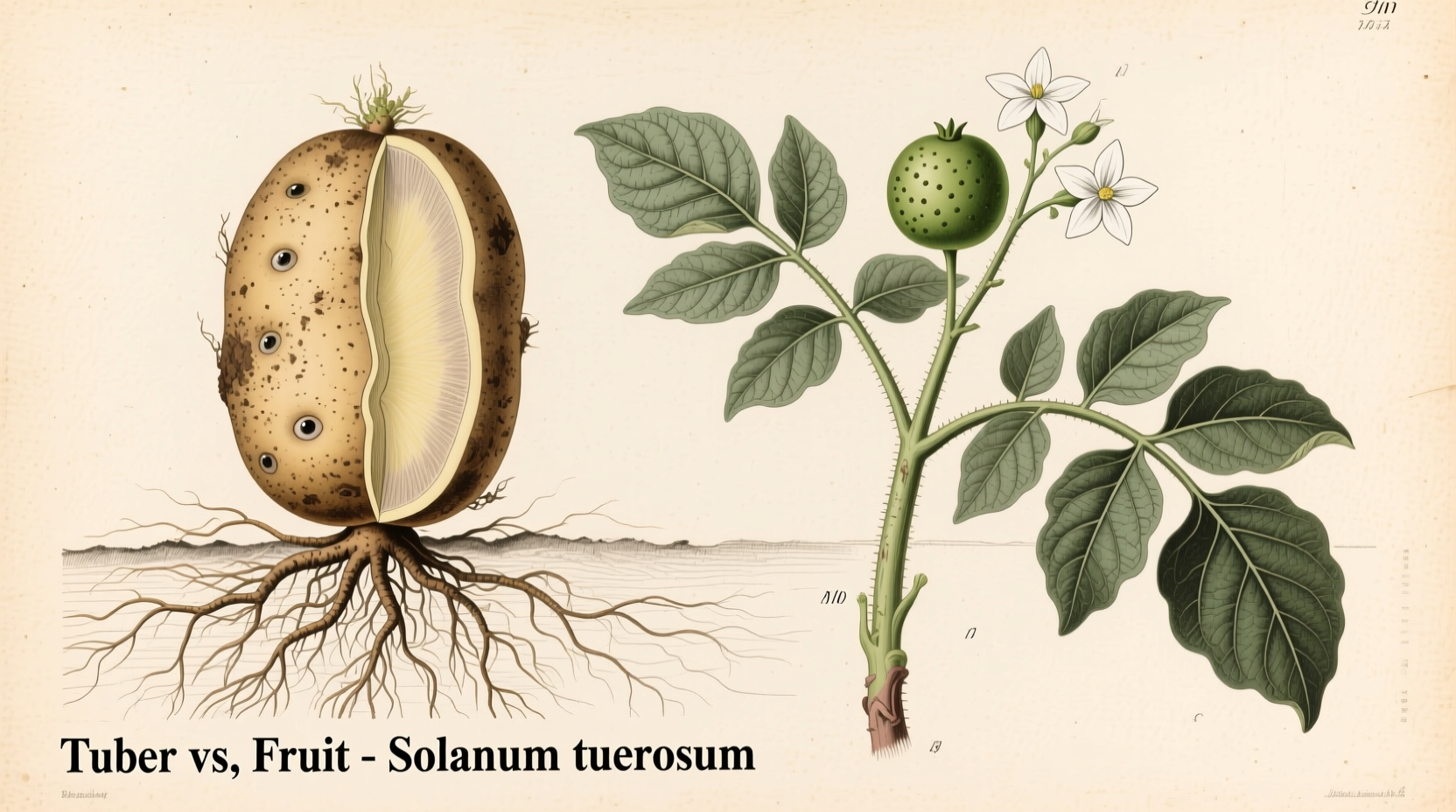

Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), however, develop differently. What we eat is the plant's underground stem modification called a tuber, not a seed-bearing structure. These tubers store energy for the plant and lack seeds entirely. The actual fruit of the potato plant—small, green, and tomato-like—contains toxic compounds and isn't consumed.

Understanding Food Classification Systems

The confusion around whether potato is a fruit or vegetable stems from two distinct classification systems:

| Classification System | Definition Criteria | Where Potatoes Fit |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical | Plant structure and development | Tuber (modified stem) |

| Culinary | Flavor profile and cooking usage | Starchy vegetable |

| Nutritional | Vitamin/mineral composition | Carbohydrate source |

Why This Confusion Persists

Many commonly consumed "vegetables" are botanically fruits, creating understandable confusion. Tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers all develop from flowers and contain seeds—making them fruits scientifically. The 1893 Nix v. Hedden Supreme Court case even legally classified tomatoes as vegetables for tariff purposes, highlighting how context affects categorization.

Potatoes represent the opposite scenario—they're consistently vegetables in all classification systems. Unlike tomatoes, they never develop from flowering plant ovaries. This distinction matters for gardeners tracking plant life cycles and chefs understanding ingredient behavior during cooking.

Practical Implications of Proper Classification

Understanding is potato considered a fruit has real-world applications:

- Gardening: Potato tubers grow from underground stems (stolons), not roots. This affects planting depth and soil requirements compared to root vegetables like carrots.

- Cooking: As starch-rich tubers, potatoes behave differently than fruits during cooking—they don't caramelize like fruit sugars but gelatinize when heated.

- Nutrition: Potatoes provide complex carbohydrates and potassium, unlike fruits which typically offer more simple sugars and vitamin C.

Historical Context of Potato Classification

The potato's classification journey reveals how scientific understanding evolves:

- 1530s: Spanish explorers bring potatoes from South America, initially classifying them as truffles due to similar appearance

- 1753: Carl Linnaeus formally classifies potatoes as Solanum tuberosum in Species Plantarum, establishing their botanical identity

- 1840s: Botanists confirm potatoes develop from modified stems rather than roots or fruits

- Present: USDA and agricultural authorities consistently categorize potatoes as vegetables in dietary guidelines

This historical progression demonstrates why reliable sources like the USDA's plant database remain essential for accurate food classification.

When Classification Matters Most

The distinction between potato fruit or vegetable becomes crucial in specific contexts:

- Seed saving: True potato seeds come from the plant's actual fruit (not the tuber), requiring different harvesting techniques

- Pest management: Tuber-specific pests like Colorado potato beetles require different control than fruit-targeting insects

- Nutrition planning: Dietary guidelines group potatoes with vegetables for meal planning, though their carb content resembles grains

For most home cooks, the botanical distinction has minimal impact—potatoes function as vegetables in recipes regardless of technical classification. However, gardeners and agricultural professionals must understand these differences for successful cultivation.

Common Misconceptions Addressed

Several myths persist about potato classification:

- Myth: "Potatoes grow underground, so they must be roots like carrots"

Fact: Potatoes are stem modifications (tubers), while carrots are true roots. Tubers have "eyes" (buds) that can sprout new plants. - Myth: "If tomatoes are fruits, potatoes must be too"

Fact: Tomatoes develop from flowers and contain seeds; potatoes develop from stem tissue and store energy. - Myth: "Sweet potatoes are related to regular potatoes"

Fact: Sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) are root vegetables in a different plant family than white potatoes.

Practical Takeaways for Home Cooks and Gardeners

Whether you're meal planning or planting your garden, these guidelines help apply this knowledge:

- Store potatoes in cool, dark places (not refrigerators) to prevent sprouting and chemical changes

- When planting, use seed potatoes (tubers) rather than seeds from the plant's fruit for reliable results

- In cooking, treat potatoes as starch components rather than fruit-based ingredients

- For balanced nutrition, pair potatoes with actual vegetables to increase vitamin diversity

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4