The Botanical Truth Behind Your Kitchen Staple

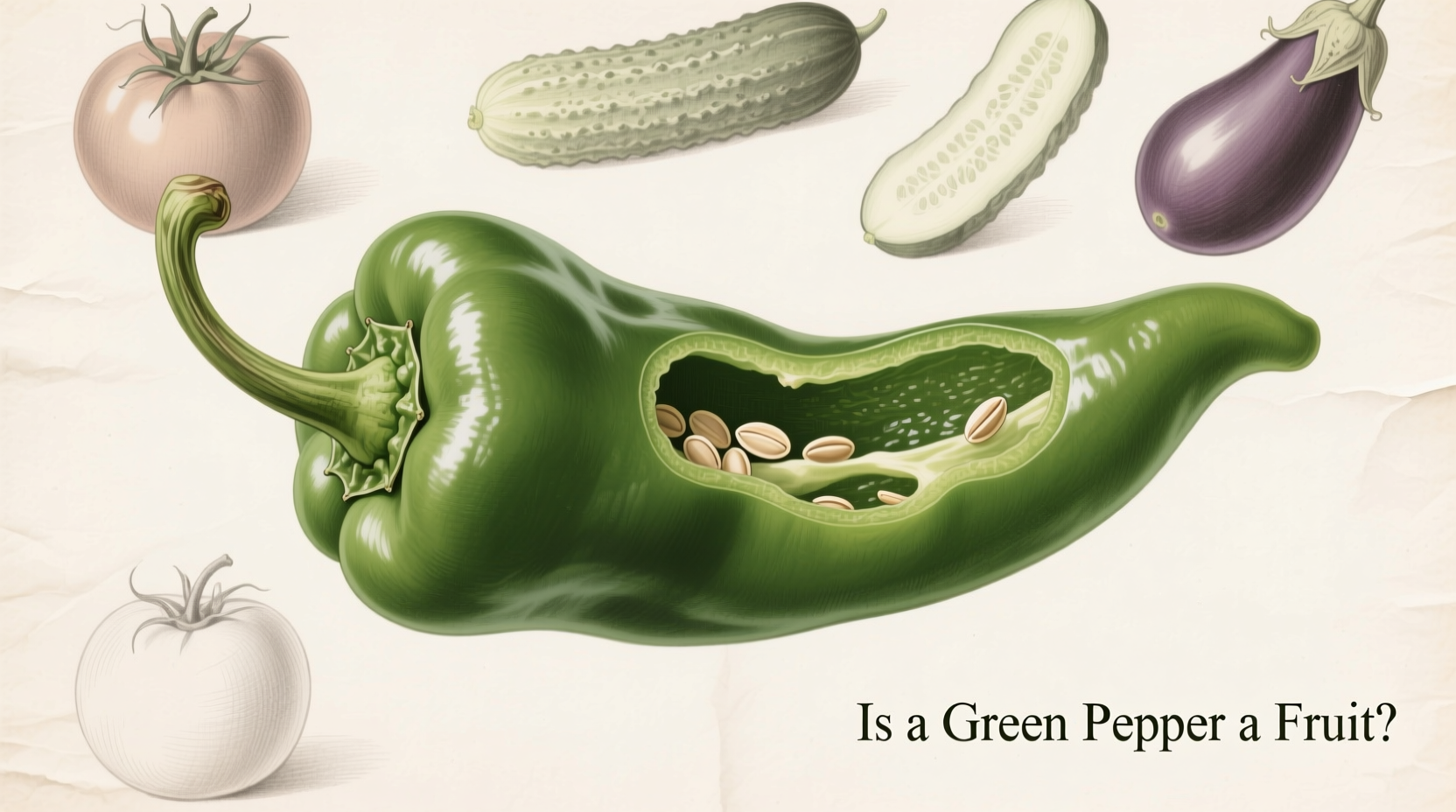

When you're chopping green peppers for your stir-fry or salad, you're actually handling a fruit—not in the sweet, dessert sense, but according to strict botanical classification. This surprising fact explains why grocery stores often place bell peppers in the vegetable section while botanists categorize them differently.

Why Botanists Call Peppers Fruits

The botanical definition of a fruit is simple: it's the mature ovary of a flowering plant, usually containing seeds. By this scientific standard, peppers unquestionably qualify as fruits. When a pepper flower is pollinated, the ovary swells and develops into what we recognize as the pepper, with seeds nestled inside.

"Many common 'vegetables' like tomatoes, cucumbers, and eggplants are actually fruits botanically," explains Maya Gonzalez, a Latin American cuisine specialist with a decade of research on indigenous spice traditions. "This classification confusion stems from the difference between scientific terminology and culinary tradition."

From Flower to Harvest: The Pepper's Natural Timeline

Understanding the pepper's development timeline clarifies why green peppers specifically create confusion:

- Flowering stage: White or purple flowers appear on the pepper plant

- Pollination: Bees transfer pollen, triggering fruit development

- Early fruit stage (green peppers): Harvested before full ripening, containing chlorophyll that gives green color

- Ripening process: Left on the plant, green peppers transform through yellow and orange stages

- Full maturity: Eventually becomes red, yellow, or orange depending on variety, with increased sugar content

Green peppers are simply unripe versions of what will become red, yellow, or orange peppers. This early harvest explains their sharper, more bitter taste compared to their sweeter, fully ripened counterparts.

Botanical vs. Culinary Classification: A Clear Comparison

| Food Item | Botanical Classification | Culinary Classification | Reason for Culinary Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green pepper | Fruit | Vegetable | Savory flavor, used in main dishes rather than desserts |

| Tomato | Fruit | Vegetable | Historically classified as vegetable by US Supreme Court (Nix v. Hedden, 1893) |

| Cucumber | Fruit | Vegetable | Used in salads and savory preparations |

| Strawberry | Fruit | Fruit | Sweet flavor profile, used in desserts |

Practical Implications for Home Cooks

While the botanical classification might seem academic, it has real kitchen consequences. The fruit nature of peppers explains several practical cooking considerations:

- Ripening after harvest: Unlike true vegetables, peppers continue ripening off the plant. Store green peppers at room temperature for 2-3 days to encourage color change and sweetness development

- Nutritional differences: As green peppers ripen to red, their vitamin C content increases by up to 30% and they develop higher levels of antioxidants like beta-carotene

- Cooking behavior: The fruit structure means peppers contain more natural sugars than true vegetables, affecting caramelization and browning during cooking

- Storage considerations: Being fruits, peppers are more sensitive to ethylene gas from other produce, which can accelerate ripening or spoilage

Why the Confusion Persists

The disconnect between scientific and culinary classification dates back to 1893, when the US Supreme Court ruled in Nix v. Hedden that tomatoes should be taxed as vegetables despite their botanical classification as fruits. This legal precedent established that culinary usage, not botanical accuracy, determines how foods are treated in commerce and cooking.

Peppers followed a similar path. The USDA's FoodData Central database categorizes peppers in the vegetable group for nutritional purposes, reflecting how they're predominantly used in American cuisine. This practical approach helps with dietary guidelines, even if it contradicts botanical science.

When Classification Actually Matters

For most home cooking, whether you consider peppers fruits or vegetables won't affect your recipes. However, this distinction becomes important in specific contexts:

- Gardening: Understanding peppers as fruits helps with proper pollination techniques and harvesting timing

- Nutrition planning: Recognizing that riper peppers (red, yellow) offer more nutritional benefits than green ones

- Food preservation: Fruit characteristics affect how peppers respond to canning and pickling processes

- Culinary competitions: Some professional cooking competitions have strict definitions for fruit-based versus vegetable-based dishes

Setting the Record Straight on Common Misconceptions

Several myths persist about pepper classification:

- Myth: "Green peppers are a different plant species than red peppers"

- Fact: They're the same plant at different ripeness stages—green peppers are simply unripe versions

- Myth: "Only sweet fruits like apples qualify as botanical fruits"

- Fact: Botanical fruit classification depends solely on plant structure, not taste

- Myth: "If it's called a 'vegetable' in cooking, it must be botanically a vegetable"

- Fact: Culinary classification is based on flavor and usage, not plant biology

The next time you're at the farmers market, remember that those crisp green peppers are technically fruits in their early developmental stage—nature's clever packaging for pepper seeds, designed to be eaten and dispersed by animals.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4