The Irish Potato Famine was primarily caused by a devastating plant disease called Phytophthora infestans (potato blight) that destroyed Ireland's potato crops from 1845-1852. However, the catastrophe's severity resulted from a combination of biological, political, and socioeconomic factors including Ireland's extreme dependence on potatoes, British colonial policies, absentee landlordism, and inadequate government relief efforts during the crisis.

Understanding what caused the Irish Potato Famine requires examining both the immediate biological disaster and the underlying conditions that turned crop failure into a human catastrophe. Between 1845 and 1852, Ireland lost approximately one million people to starvation and disease while another million emigrated, permanently altering the island's demographic landscape. This comprehensive analysis reveals how a natural disaster became a historic tragedy through the intersection of agricultural vulnerability, colonial economics, and policy failures.

The Biological Trigger: Potato Blight Arrives

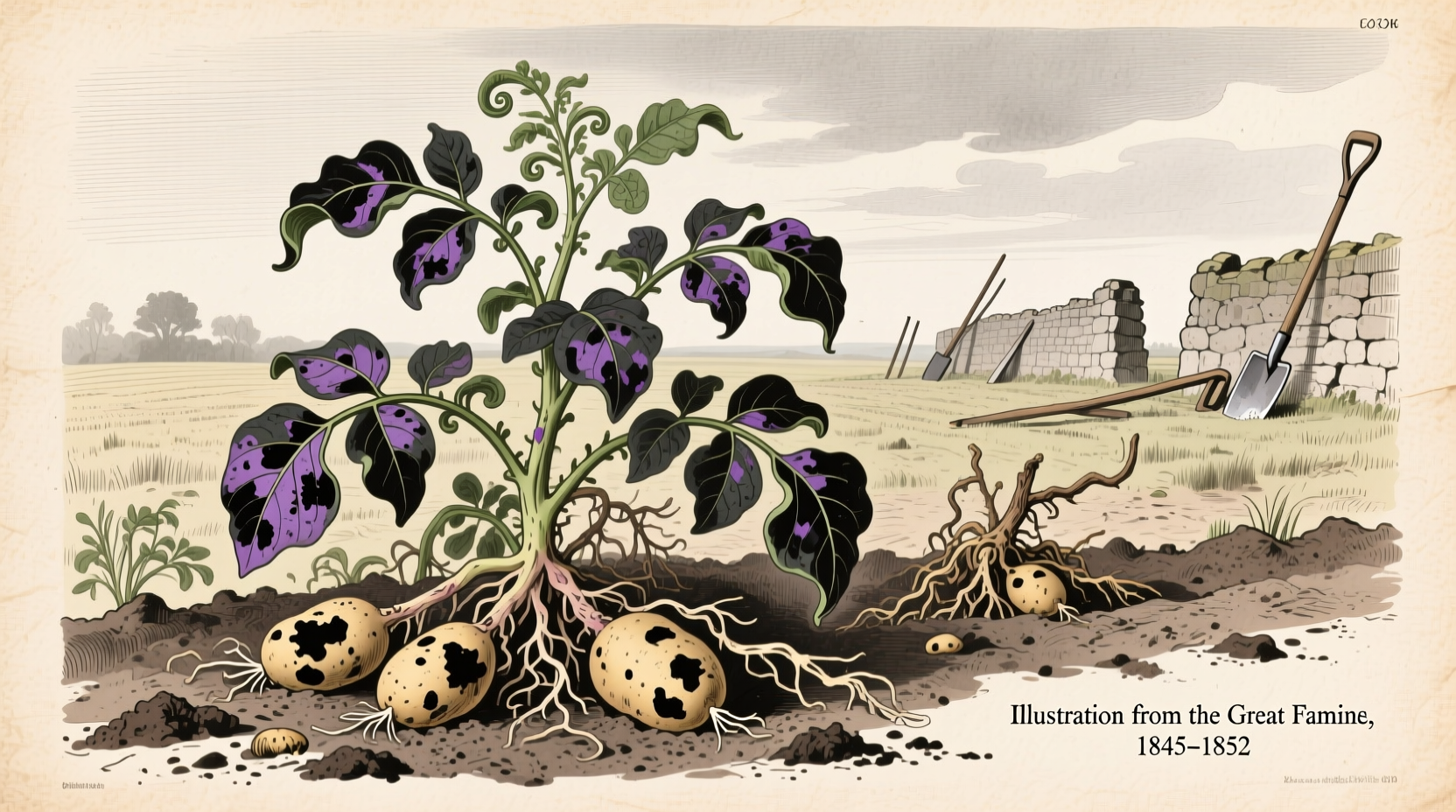

When farmers inspected their potato fields in September 1845, they discovered something unprecedented—leaves covered in a mysterious white mold that quickly turned black and withered. Within days, the infection spread to the tubers underground, transforming what should have been a bountiful harvest into inedible, rotten masses. Modern science identifies this as Phytophthora infestans, a water mold that thrives in cool, damp conditions.

Unlike other European countries affected by the same blight, Ireland suffered disproportionately because:

- Over one-third of Ireland's population relied almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance

- Ireland's potato varieties lacked genetic diversity, making them uniformly vulnerable

- Crop rotation practices were minimal due to land constraints

- There were no effective fungicides or agricultural countermeasures available at the time

Why Potatoes Dominated Irish Agriculture

To understand why the blight caused such devastation, we must examine Ireland's agricultural dependence on potatoes. By the 1840s, the potato had become the staple food for approximately 3 million Irish people—nearly half the population. This dependence wasn't accidental but resulted from systematic economic conditions:

| Factor | Impact on Potato Dependence |

|---|---|

| Land Tenure System | Tenants paid rent in cash crops (grain, livestock), leaving small plots for subsistence farming where potatoes thrived |

| Nutritional Value | One acre of potatoes could feed a family of six, providing complete nutrition with minimal space |

| Population Growth | Ireland's population doubled between 1780-1840, increasing pressure on limited farmland |

| Economic Restrictions | British trade policies limited Irish agricultural diversification options |

Political and Economic Vulnerabilities

The biological disaster became a humanitarian catastrophe due to Ireland's political and economic circumstances under British rule. Several interconnected factors created perfect conditions for disaster:

Absentee Landlord System

Approximately 60% of Irish agricultural land was owned by absentee landlords, mostly residing in England. This created a disconnect between landowners and tenants, with rents often consuming 30-60% of a tenant's income. When crops failed, landlords frequently evicted tenants unable to pay, worsening the crisis.

British Government Policy Failures

Despite Ireland continuing to export substantial quantities of grain, meat, and dairy to Britain during the famine years, the British government adhered to laissez-faire economic principles that limited intervention. Key policy failures included:

- Slow initial response to the 1845 crop failure

- Repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, which removed tariffs on imported grain but came too late for the starving population

- Reliance on inadequate public works programs that paid starvation wages

- Termination of soup kitchens in 1847, replaced by workhouse systems that many couldn't reach

Timeline of the Famine Crisis

The progression from crop failure to national catastrophe followed a tragic pattern across multiple years:

| Year | Key Events | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | First appearance of potato blight in Ireland; 1/3 of crop destroyed | Initial food shortages; government establishes Royal Irish Relief Commission |

| 1846 | Complete crop failure; 3/4 of potato harvest lost | Widespread starvation; British government ends soup kitchens, shifts to workhouse system |

| 1847 | "Black '47" - worst year of famine; partial crop recovery fails | Peak mortality; mass evictions; typhus epidemic spreads |

| 1848-1852 | Recurring crop failures; continued emigration | Population decline continues; long-term demographic changes become permanent |

Common Misconceptions About Famine Causes

Several persistent myths obscure the true causes of the Irish Potato Famine. Historical research from Trinity College Dublin and the National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park has helped clarify these misunderstandings:

- Myth: The famine was solely a natural disaster Reality: While blight triggered the crisis, political and economic factors determined its severity

- Myth: Ireland had no food during the famine Reality: Ireland continued exporting substantial quantities of grain, meat, and dairy throughout the famine years

- Myth: The British government did nothing Reality: Relief efforts existed but were inadequate, poorly administered, and often counterproductive

- Myth: Only potatoes failed Reality: Other crops succeeded but were largely exported or inaccessible to the starving population

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The Irish Potato Famine reshaped Ireland's demographic, cultural, and political landscape permanently. According to research from the Department of Economic History at the London School of Economics, Ireland's population declined from approximately 8.2 million in 1841 to 6.6 million by 1851, with continued decline in subsequent decades.

Key long-term impacts include:

- Mass emigration that established large Irish communities in America, Canada, and Australia

- Transformation of Irish agriculture toward pasture-based livestock farming

- Deepening of Irish resentment toward British rule, fueling later independence movements

- Changes in land ownership patterns through the Encumbered Estates Act of 1849

- Development of more diverse agricultural practices to prevent future single-crop dependence

Modern historians increasingly view the famine not as an unavoidable natural disaster but as a preventable tragedy exacerbated by political choices. As Professor Christine Kinealy of Quinnipiac University notes in her research published by the National Library of Ireland, "The famine was not just about the failure of the potato crop, but about the failure of government to respond adequately to a crisis it had the resources to mitigate."

Understanding the Famine in Historical Context

When examining what caused the Irish Potato Famine, it's essential to recognize the complex interplay of factors that transformed a biological event into a human catastrophe. The famine serves as a powerful historical case study in how natural disasters interact with social, economic, and political systems.

For those seeking to understand this pivotal moment in Irish history, primary sources from the British Parliamentary Papers and the National Archives of Ireland provide invaluable documentation of the period. These records reveal both the scale of the tragedy and the policy decisions that shaped its course.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4