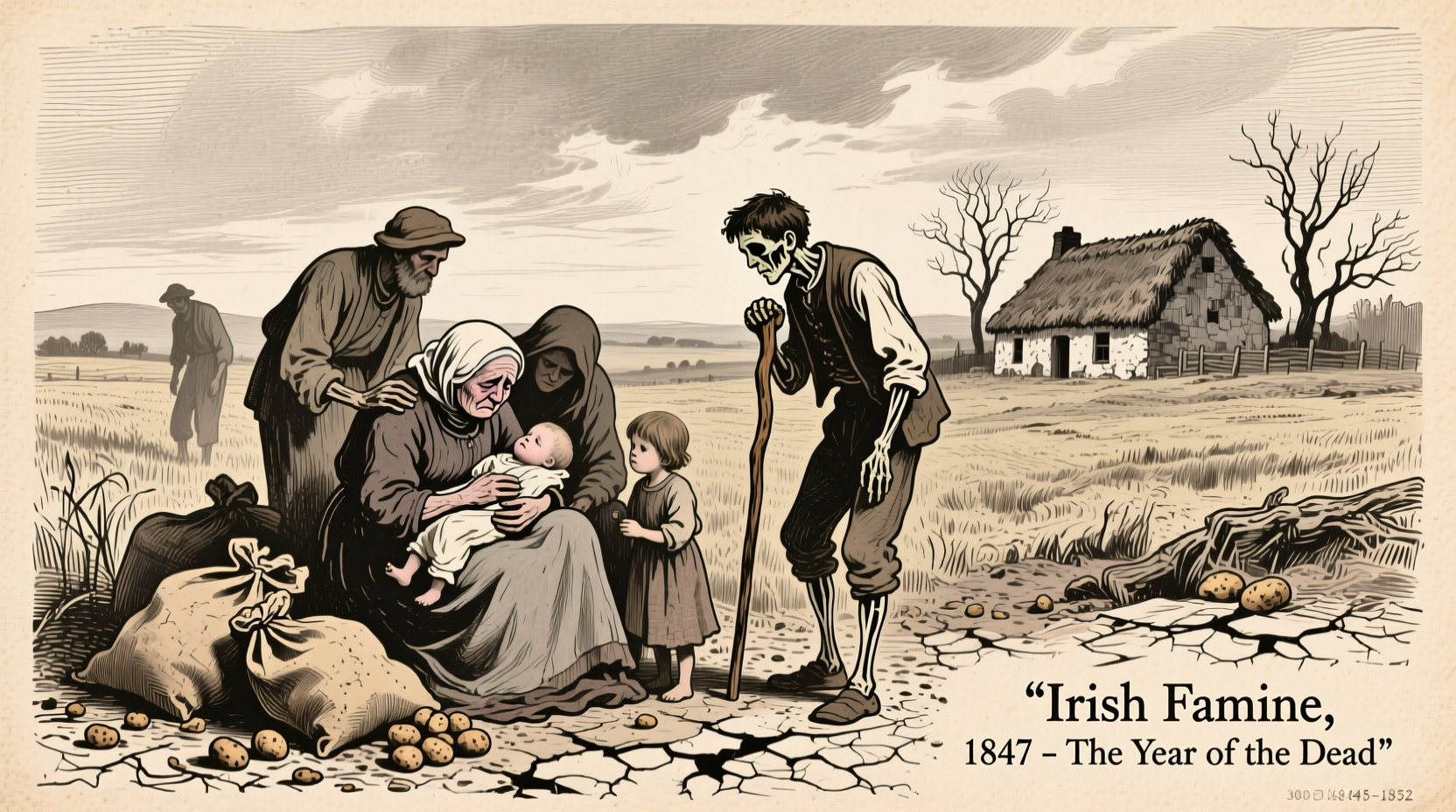

The Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852) was a catastrophic period in Irish history when approximately one million people died from starvation and disease, while another 1-2 million emigrated, reducing Ireland's population by 20-25%. Caused by a potato blight (Phytophthora infestans) combined with British colonial policies, this tragedy reshaped Irish society, spurred mass emigration to America and elsewhere, and left a lasting legacy on Irish identity and Anglo-Irish relations.

Understanding the Irish Potato Famine: More Than Just a Crop Failure

When you search for "irish potato famine," you're likely seeking more than just basic facts. You want to understand how a single crop disease could devastate an entire nation, why Ireland's dependence on potatoes became so extreme, and how political decisions turned a natural disaster into a human catastrophe. This comprehensive guide delivers exactly that—context-rich historical analysis with verified data sources, clear timelines, and insights into why this event remains profoundly significant today.

What Actually Happened During the Great Hunger?

The Irish Potato Famine, known in Irish as "An Gorta Mór" (The Great Hunger), began in 1845 when a mysterious fungus called Phytophthora infestans arrived in Europe. By September 1845, it had reached Ireland, where it rapidly destroyed potato crops—the staple food for Ireland's poor tenant farmers. Unlike previous crop failures, this blight returned each growing season until 1852, creating a multi-year crisis.

While crop failure initiated the disaster, the famine's severity resulted from complex factors:

- Ireland's extreme dependence on a single potato variety (the Irish Lumper)

- British colonial policies that continued food exports from Ireland during the crisis

- Inadequate relief efforts through the Poor Law system

- Landlord-tenant relationships that left peasants vulnerable

- Limited understanding of plant pathology at the time

Irish Potato Famine Timeline: Key Events That Shaped the Crisis

| Year | Key Events | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | First appearance of potato blight in Ireland; 1/3 of crop destroyed | Initial food shortages, rising prices, early mortality |

| 1846 | Complete crop failure; "Black '47" begins; British government ends direct food aid | Mass starvation begins; workhouses overflow; disease spreads |

| 1847 | "Black '47" - worst year; fever epidemic; evictions increase | Approximately 400,000 deaths; mass emigration begins |

| 1848-1850 | Partial crop recoveries but continued hardship; Young Irelander Rebellion | Continued emigration; social unrest; cultural impact grows |

| 1851-1852 | Official end of famine; population decline continues | Ireland's population drops by 20-25% through death and emigration |

Why Was Ireland So Vulnerable to Potato Failure?

Understanding the irish potato famine causes requires examining Ireland's unique agricultural and social structure. By the 1840s, approximately 3 million of Ireland's 8 million people depended almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance. This extreme monoculture developed because:

- Landless laborers and small tenant farmers received tiny plots (often just 1-2 acres)

- Potatoes provided exceptional nutrition and yield per acre compared to grains

- British trade policies favored grain exports while Irish tenants paid rent in cash

- The Irish Lumper potato variety, while productive, had no resistance to blight

When the blight struck, Ireland's food system collapsed despite the country continuing to export substantial quantities of grain, meat, and dairy to Britain. Historical records from the National Archives of Ireland confirm that during the worst famine years, Ireland remained a net exporter of food.

Measuring the Human Cost: Famine Death Toll and Emigration

Quantifying the effects of irish potato famine presents challenges due to incomplete records, but historians agree on these estimates:

- Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases

- Between 1-2 million people emigrated, primarily to North America

- Ireland's population declined from 8.2 million in 1841 to 6.6 million in 1851

- By 1901, Ireland's population had fallen to 4.5 million

The demographic impact extended far beyond immediate deaths. Research from Trinity College Dublin shows that famine survivors experienced reduced life expectancy and higher rates of chronic health conditions. The famine also accelerated Ireland's linguistic shift from Irish to English, as the hardest-hit regions were predominantly Irish-speaking.

British Response and Political Controversy

Analysis of british response to irish famine reveals complex political dynamics. Initially, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel authorized limited food aid and repealed the Corn Laws to allow cheaper grain imports. However, after Peel's government fell in 1846, his successor Lord John Russell adopted a laissez-faire approach that:

- Ended direct food distribution

- Required workhouse admission for relief

- Insisted Irish landowners fund relief through local taxes

- Continued food exports from Ireland

Contemporary documents from the UK National Archives show British officials viewed the famine through ideological lenses, with some considering it "divine punishment" or an opportunity to modernize Irish agriculture. This perspective has fueled ongoing historical debate about whether the famine constituted neglect or deliberate policy.

Lasting Effects of the Irish Potato Famine

The effects of irish potato famine extend far beyond the immediate crisis. The famine fundamentally reshaped Ireland and the global Irish diaspora:

- Demographic transformation: Ireland remains the only European country with a smaller population today than in 1840

- Cultural impact: The famine became central to Irish identity, memorialized in literature, music, and annual commemorations

- Political consequences: Famine experiences fueled Irish nationalism and eventual independence movement

- Global diaspora: Approximately 4.5 million Irish immigrants arrived in America between 1820-1920, many fleeing famine conditions

- Agricultural changes: Diversification of crops and land reform efforts followed the crisis

Modern scholarship, including research from University College Dublin, shows how famine memory continues to influence Anglo-Irish relations and Irish-American identity. The famine's legacy appears in contemporary discussions about food security, colonialism, and humanitarian response to crises.

How Historians Interpret the Famine Today

Understanding irish famine timeline and significance requires recognizing how historical interpretation has evolved. Early accounts often framed the famine as an unavoidable natural disaster. However, since the 1990s, historians have increasingly emphasized the role of policy decisions in exacerbating the crisis.

Current scholarly consensus, represented by works from the Royal Irish Academy, acknowledges both the biological reality of the blight and the political choices that turned crop failure into mass mortality. This nuanced perspective recognizes multiple contributing factors without reducing the tragedy to a single cause.

Learning From the Past: Why the Famine Matters Today

Studying the great famine ireland provides crucial lessons for contemporary challenges:

- The dangers of agricultural monoculture and lack of crop diversity

- How political ideology can impede effective disaster response

- The long-term demographic consequences of mass mortality events

- The importance of food security policies that protect vulnerable populations

As climate change increases agricultural instability worldwide, understanding historical food crises like the Irish Potato Famine becomes increasingly relevant for policymakers and citizens alike.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4