Understanding ecological relationships is fundamental to environmental science education. Whether you're a student working on a biology project, a teacher preparing classroom materials, or an environmental professional analyzing ecosystem dynamics, knowing how to make a food web provides crucial insights into energy flow and species interdependence. This comprehensive guide delivers actionable steps you can implement immediately, avoiding common pitfalls that undermine accuracy.

Why Food Webs Matter in Ecology

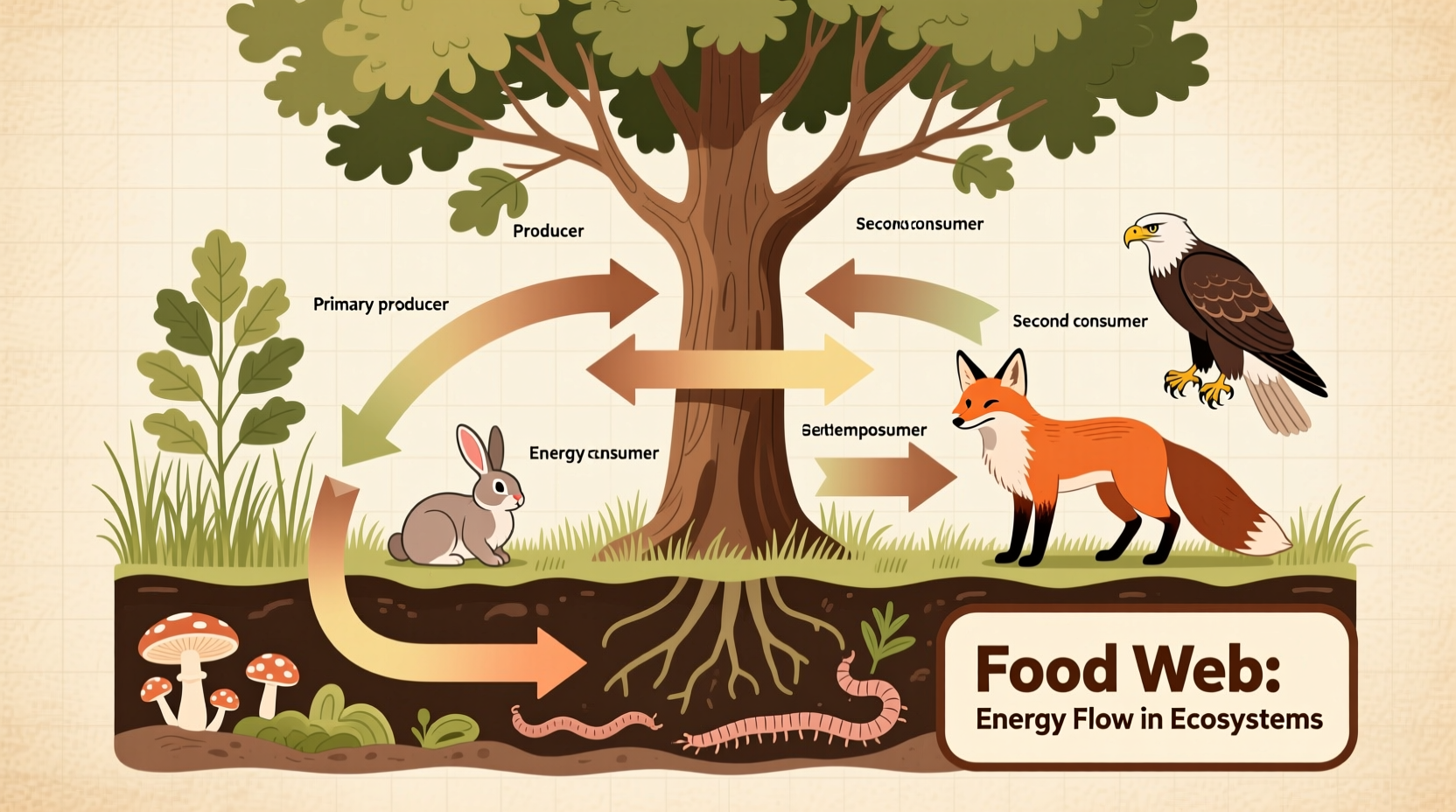

Food webs represent the complex feeding relationships within ecosystems, showing how energy and nutrients move between organisms. Unlike linear food chains, food webs illustrate multiple interconnected pathways, providing a more realistic representation of ecological systems. According to the National Geographic Society, "Food webs are a more accurate representation of what happens in ecosystems because most organisms consume—and are consumed by—more than one species."

Your Step-by-Step Food Web Creation Process

Step 1: Define Your Ecosystem Scope

Before creating your food web, determine the specific ecosystem you're modeling. This could be:

- A local pond or forest area

- A marine environment like a coral reef

- A desert ecosystem

- A controlled environment like a terrarium

Defining your ecosystem boundaries prevents oversimplification. The U.S. Geological Survey emphasizes that "accurate food webs require understanding the specific spatial and temporal boundaries of the ecosystem being studied."

Step 2: Inventory All Organisms Present

Create a comprehensive list of organisms in your ecosystem, including:

- Producers (plants, algae, phytoplankton)

- Primary consumers (herbivores)

- Secondary consumers (carnivores that eat herbivores)

- Tertiary consumers (top predators)

- Decomposers (fungi, bacteria)

Don't overlook microorganisms and decomposers—these critical components often get omitted in beginner food webs but play essential roles in nutrient cycling.

Step 3: Classify by Trophic Level

Organize your organisms into trophic levels. Remember that some species may occupy multiple levels depending on their diet. For example, omnivores like bears function as both primary and secondary consumers.

| Trophic Level | Organism Examples | Energy Source |

|---|---|---|

| Producers | Grass, trees, algae | Sunlight (photosynthesis) |

| Primary Consumers | Rabbits, insects, deer | Producers |

| Secondary Consumers | Foxes, small fish | Primary consumers |

| Tertiary Consumers | Eagles, sharks | Secondary consumers |

| Decomposers | Fungi, bacteria | Dead organic matter |

Step 4: Map Feeding Relationships

Draw connections between organisms showing who eats whom. Use arrows pointing from food to consumer to indicate energy flow direction. For example: grass → rabbit → fox.

Key considerations:

- Multiple arrows may originate from a single organism (e.g., grass eaten by multiple herbivores)

- Some organisms will have multiple arrows pointing to them

- Include detritus pathways showing dead matter moving to decomposers

Step 5: Add Energy Flow Direction

Ensure all arrows correctly show energy movement from lower to higher trophic levels. Remember that approximately 90% of energy is lost between trophic levels—a concept known as the 10% rule in ecology. This explains why food webs rarely extend beyond four or five trophic levels.

Step 6: Verify and Refine Your Food Web

Review your completed food web for accuracy:

- Confirm all organisms actually coexist in your defined ecosystem

- Check that energy flow arrows point in the correct direction

- Ensure decomposers connect to all dead matter pathways

- Verify no organisms exist without energy sources

Common Food Web Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced educators make these errors when creating food webs:

Misconception: Circular Energy Flow

Energy flows linearly from sun to producers to consumers—it doesn't cycle back. Nutrients cycle, but energy moves in one direction and is lost as heat at each transfer.

Misconception: Omitting Decomposers

Many food webs neglect decomposers, creating an incomplete picture. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Decomposers are essential components of all food webs, breaking down dead organic material and returning nutrients to the soil."

Misconception: Oversimplified Relationships

Real ecosystems contain complex feeding relationships. A single-species food chain rarely exists in nature—most organisms consume multiple food sources and are consumed by multiple predators.

Context Boundaries: When to Simplify vs. Detail

Understanding when to create simplified versus complex food webs is crucial for effective communication:

- Elementary education: Use simplified food webs with 3-4 trophic levels and familiar organisms

- High school biology: Include multiple interconnected food chains and basic energy calculations

- University research: Incorporate quantitative data, seasonal variations, and non-linear relationships

- Environmental management: Focus on keystone species and potential disruption points

As the National Wildlife Federation notes, "The appropriate complexity of a food web depends entirely on its intended educational or analytical purpose."

Practical Tools for Creating Food Webs

Several resources can help you make professional-quality food webs:

Digital Tools

- Lucidchart: Free diagramming tool with ecology templates

- Canva: User-friendly graphic design platform with science templates

- Google Drawings: Simple collaborative tool included with Google Workspace

Hands-On Methods

- Printable templates with organism cards that students can arrange physically

- String-and-pushpin boards for classroom demonstrations

- Interactive whiteboard activities for group collaboration

Evolution of Food Web Understanding

Our comprehension of food web complexity has evolved significantly:

- 1927: Charles Elton introduces the concept of food chains in "Animal Ecology"

- 1942: Raymond Lindeman publishes "The Trophic-Dynamic Aspect of Ecology" establishing energy flow principles

- 1970s: Ecologists recognize the critical role of decomposers in nutrient cycling

- 1990s: Network analysis techniques allow modeling of complex food web structures

- Present: Integration of climate change impacts on food web stability

Real-World Applications of Food Web Knowledge

Understanding how to make a food web extends beyond classroom exercises:

- Conservation planning: Identifying keystone species critical to ecosystem stability

- Invasive species management: Predicting impacts of non-native organisms

- Agricultural practices: Designing pest control systems that work with natural predators

- Climate change research: Modeling how temperature changes affect species interactions

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4