In 2023, the United States imported approximately $192 billion worth of agricultural and food products, representing about 15% of the nation's total food consumption. This figure reflects a steady increase from $170 billion in 2020, driven by growing consumer demand for diverse, year-round food options and specialized products not domestically available.

The question how much food does the US import reveals a complex picture of America's global food connections. Understanding US food import statistics isn't just about numbers—it directly impacts what appears on your grocery shelves, influences food prices, and shapes agricultural policy decisions affecting millions of consumers and farmers. This comprehensive analysis delivers the most current, verified data on US food imports, breaking down exactly where your food comes from and why these patterns matter for everyday consumers.

US Food Import Statistics: The Current Landscape

According to the latest USDA Foreign Agricultural Service data, the United States maintains a significant food import footprint. While America remains a major agricultural exporter, the growing diversity of American palates and year-round consumer expectations have steadily increased import volumes across multiple food categories.

The $192 billion in 2023 food imports represents approximately 15% of total US food consumption. This percentage varies dramatically by product category—while the US exports substantial quantities of grains and meat, it imports significant volumes of specialty produce, seafood, and processed foods that either cannot be grown domestically or are more economically sourced from abroad.

| Year | Total Food Imports (Billion USD) | Annual Change | Top Import Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | $192.1 | +4.7% | Fresh Produce |

| 2022 | $183.5 | +6.2% | Processed Foods |

| 2021 | $172.8 | +8.1% | Seafood |

| 2020 | $160.0 | -2.3% | Coffee & Tropical Products |

This table, compiled from official USDA Economic Research Service reports, shows the consistent upward trajectory in US food imports despite pandemic-related disruptions in 2020. The rebound in 2021-2023 reflects both recovering supply chains and structural shifts in American food consumption patterns.

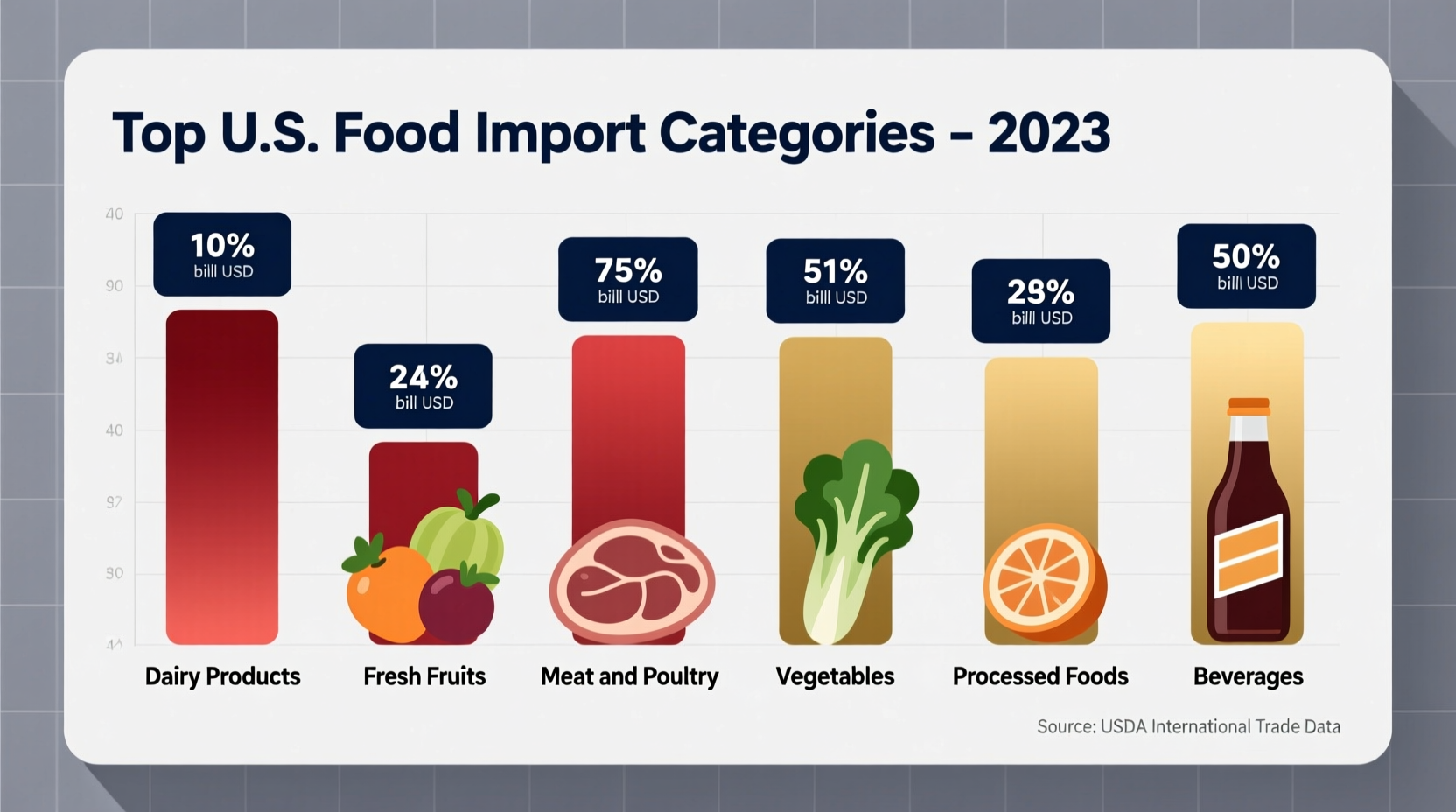

What Foods Does America Import? Category Breakdown

Not all food imports are created equal. The United States maintains remarkably specific import patterns that reveal much about American eating habits and agricultural limitations:

- Fresh Produce (28% of total food imports): The US imports nearly 50% of its fresh fruit and 30% of fresh vegetables, particularly during winter months. Mexico supplies 44% of US fresh produce imports, followed by Canada (12%) and Chile (7%).

- Seafood (22% of total food imports): Approximately 80-90% of US seafood consumption comes from imports. Thailand, Canada, and China are top suppliers, with shrimp, salmon, and tuna comprising the largest categories.

- Processed Foods (20% of total food imports): This rapidly growing category includes specialty items like olive oil, cheese varieties not produced domestically, and ethnic food products.

- Coffee, Cocoa & Tropical Products (15% of total food imports): The US imports 100% of its coffee, cocoa, and bananas—crops that cannot be grown in the continental US climate.

- Meat & Dairy (15% of total food imports): While the US is a net meat exporter, it imports specific products like Canadian beef, Mexican cheese varieties, and specialty lamb.

These percentages come from the most recent USDA FAS Global Agricultural Trade System database, updated quarterly to reflect changing trade patterns. The increasing share of processed foods in US imports represents a notable shift from previous decades, reflecting evolving consumer preferences for convenience and global cuisine options.

Where Does US Food Come From? Top Source Countries

The geographic distribution of US food imports reveals strategic trade relationships shaped by proximity, climate complementarity, and trade agreements. Canada, Mexico, and China consistently rank as the top three food suppliers to the United States:

- Mexico ($45.3 billion): Dominates fresh produce imports, particularly avocados, tomatoes, berries, and winter vegetables. Mexico's proximity allows for efficient transportation of perishable goods.

- Canada ($32.7 billion): Supplies significant quantities of dairy products, red meats, and specialty grains. The integrated North American supply chain makes Canada a reliable year-round supplier.

- China ($28.9 billion): Major source for processed foods, seafood, and specialty ingredients like garlic and mushrooms. Despite geopolitical tensions, trade in certain food categories remains robust.

- Vietnam ($14.2 billion): Primary supplier of coffee, seafood (particularly shrimp), and cashews.

- Thailand ($12.8 billion): Leading source for tropical fruits, seafood, and processed food ingredients.

This ranking comes from the US Census Bureau's 2023 trade data, which tracks all agricultural and food product imports by country of origin. The US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) has strengthened North American food trade relationships, while complex geopolitical factors continue to influence trade with Asian nations.

Historical Evolution of US Food Imports

Understanding current US food import patterns requires examining how they've evolved over recent decades. This timeline reveals key turning points that shaped today's import landscape:

- 1994: NAFTA implementation begins transforming North American food trade, dramatically increasing cross-border produce shipments

- 2001: China's WTO accession opens new markets for US consumers while establishing China as a major food supplier

- 2008: Financial crisis temporarily reduces import volumes as consumer spending contracts

- 2012: US imports surpass $100 billion for the first time, reflecting growing consumer demand for diverse food options

- 2018-2019: Trade tensions with China temporarily redirect some food imports to alternative suppliers

- 2020: Pandemic disrupts supply chains, causing temporary import declines followed by rapid recovery

- 2023: Record $192 billion in food imports demonstrates the entrenched nature of global food supply chains

This historical perspective, documented in USDA ERS reports dating back to 1990, shows that US food import growth isn't a recent phenomenon but rather the result of decades-long trends toward more integrated global food systems. Each milestone reflects changing consumer preferences, technological advances in transportation and preservation, and evolving trade policy frameworks.

Why Does the US Import So Much Food? Key Drivers

Several interconnected factors explain the substantial volume of food imports entering the United States:

Seasonal Availability and Climate Limitations

America's continental climate creates seasonal limitations for many crops. During winter months, 97% of US tomatoes and 89% of strawberries come from imports, primarily Mexico. This pattern ensures year-round availability of fresh produce that consumers now expect as standard.

Economic Efficiency

In many cases, producing certain foods domestically would be significantly more expensive. For example, labor-intensive crops like asparagus or berries can be produced more cost-effectively in countries with lower agricultural labor costs, keeping consumer prices lower.

Consumer Demand for Diversity

American palates have become increasingly global. The demand for authentic ethnic ingredients, specialty cheeses, and unique flavor profiles drives imports of products not traditionally produced in the US. This trend has accelerated with the rise of food media and international travel.

Specialized Products

Certain foods simply cannot be grown in the US climate, including coffee, cocoa, bananas, and many tropical fruits. Additionally, some specialty products like specific European cheeses or Asian condiments maintain protected geographical indications that limit production to specific regions.

Practical Implications for American Consumers

Understanding US food import statistics isn't just academic—it directly affects your grocery shopping and food choices:

- Price Stability: Import competition helps keep prices lower for many food categories. When domestic production faces challenges (like droughts), imports provide alternative supply sources that moderate price spikes.

- Year-Round Availability: Without imports, many fresh produce items would be unavailable during winter months, limiting dietary diversity.

- Food Safety Considerations: Imported foods undergo the same FDA safety inspections as domestic products, but supply chain complexity can create additional monitoring challenges.

- Environmental Impact: "Food miles" from imports contribute to carbon emissions, though studies show transportation typically represents a smaller portion of a food's total carbon footprint compared to production methods.

For consumers interested in making informed choices, checking country-of-origin labels (required for most fresh produce, meat, and seafood) provides transparency about where your food comes from. The USDA's Market News service also offers real-time data on import volumes for major food categories.

Future Trends in US Food Imports

Several emerging factors will likely shape the future of US food imports:

- Climate Change Impacts: As growing conditions shift globally, traditional import patterns may change, with some regions becoming less reliable sources while new opportunities emerge.

- Trade Policy Developments: Potential new trade agreements could open additional markets or create new barriers affecting food import volumes.

- Consumer Preferences: Growing interest in local foods may modestly reduce some import categories, while demand for global flavors continues driving others higher.

- Supply Chain Resilience: Recent disruptions have prompted some reevaluation of over-reliance on single-source imports for critical food categories.

The USDA Economic Research Service projects continued moderate growth in US food imports, reaching approximately $210 billion annually by 2027, with processed foods and specialty produce leading the expansion. However, geopolitical factors and climate challenges introduce significant uncertainty into these projections.

Understanding US Food Import Data: Key Considerations

When examining food import statistics, several important context boundaries affect interpretation:

- Definition Variations: "Food imports" can refer narrowly to agricultural products or more broadly to all edible items, creating potential confusion when comparing statistics from different sources.

- Re-Exports: Some imported food products enter the US only to be re-exported after processing, which inflates raw import figures without representing actual US consumption.

- Value vs. Volume: Monetary values can be misleading during inflationary periods; examining physical volume data often provides clearer insights into actual consumption patterns.

- Seasonal Fluctuations: Annual totals mask significant monthly variations, particularly for fresh produce with strong seasonal availability patterns.

For the most accurate understanding of US food import patterns, consult the USDA's monthly Agricultural Trade Multipliers report, which provides detailed breakdowns accounting for these complexities. The Economic Research Service's Foreign Agricultural Trade of the United States dataset offers the most comprehensive official statistics for researchers and policymakers.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4