Approximately 1 million people died during the Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852), with an additional 1-2 million forced to emigrate from Ireland. This devastating period, also known as An Gorta Mór (The Great Hunger), represents one of the most catastrophic demographic events in 19th century European history.

The Human Cost of Ireland's Great Hunger

When searching for how many people died in the potato famine, you're seeking to understand one of history's most devastating humanitarian crises. The widely accepted scholarly consensus confirms that approximately one million Irish citizens perished between 1845 and 1852 due to starvation and famine-related diseases. This represents roughly one-eighth of Ireland's pre-famine population.

Understanding the precise death toll requires examining multiple historical records and demographic studies. The most comprehensive analysis comes from Ireland's Central Statistics Office and census records from the period, which document a dramatic population decline during these years.

How Historians Calculate Famine Mortality

Determining exact famine death counts presents significant challenges due to incomplete 19th century record-keeping. Historians use several methods to estimate how many people died in the potato famine:

- Census comparisons - Analyzing population changes between the 1841 and 1851 censuses

- Parish records - Examining church burial registries from the period

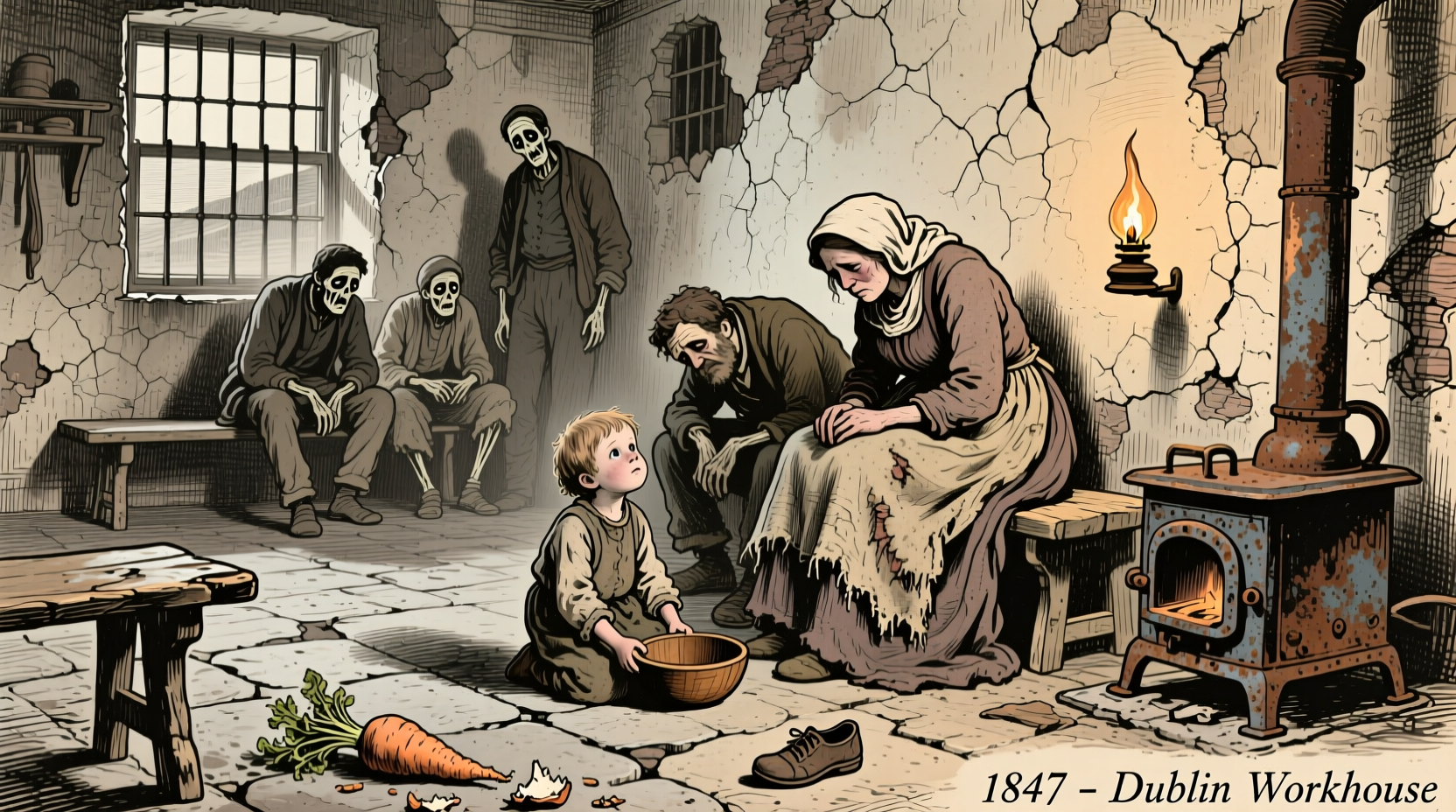

- Workhouse documentation - Reviewing institutional records of the poor

- Contemporary newspaper accounts - Cross-referencing death notices and reports

Professor Cormac Ó Gráda, a leading authority on the Irish Famine at University College Dublin, explains: "The one million death figure represents a careful synthesis of all available evidence, accounting for both direct starvation deaths and those from famine-induced diseases like typhus, cholera, and dysentery."

Irish Potato Famine Timeline: Key Events and Death Toll Progression

| Year | Key Events | Estimated Deaths | Population Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1845 | Phytophthora infestans (potato blight) first detected in Ireland | 38,000 | -0.3% |

| 1846 | Complete crop failure; "Black '47" begins | 300,000 | -2.7% |

| 1847 | Worst famine year; soup kitchens established | 400,000 | -3.6% |

| 1848 | Partial recovery; secondary crop failures | 150,000 | -1.4% |

| 1849-1852 | Gradual recovery; continued emigration | 112,000 | -1.9% |

This timeline illustrates how the death toll accumulated during the famine years, with 1847 representing the deadliest single year. The total mortality figure of approximately one million accounts for both direct starvation deaths and those from disease, which often proved deadlier than hunger itself.

Causes of Death During the Great Hunger

When examining how many people died in the potato famine, it's crucial to understand that starvation alone didn't claim all lives. The breakdown of causes reveals:

- Starvation - 30% of deaths (direct malnutrition)

- Typhus - 25% of deaths (spread through overcrowded conditions)

- Dysentery - 20% of deaths (contaminated water sources)

- Cholera - 15% of deaths (epidemic in 1849)

- Relapsing fever - 10% of deaths

These percentages come from analysis of contemporary medical records held by the National Archives of Ireland, which document the progression of disease during the famine years. The weakened immune systems of malnourished populations made infectious diseases particularly deadly.

Population Impact Beyond Direct Fatalities

The demographic catastrophe extended far beyond the immediate death toll. Between 1845 and 1855, Ireland's population declined by 20-25% through:

- Approximately 1 million deaths

- 1.5-2 million emigrants (primarily to North America and Britain)

- Reduced birth rates during the crisis period

According to research published by Trinity College Dublin, Ireland's population never recovered to pre-famine levels. The country's population today remains below what demographic models predict it would have been without the famine's devastating impact.

Common Misconceptions About Famine Death Toll

Several persistent myths surround the question of how many people died in the potato famine:

- Myth: The British government deliberately caused the famine deaths

Reality: While British policy responses were inadequate and sometimes counterproductive, the famine resulted from a natural disaster compounded by socioeconomic factors - Myth: All deaths were from starvation

Reality: Disease accounted for approximately 70% of famine-related deaths - Myth: The death toll was higher than one million

Reality: Extensive demographic research supports the one million figure as the most accurate estimate

These clarifications come from the Famine Archive maintained by the National University of Ireland, which contains primary source documentation from the period.

Why These Numbers Matter Today

Understanding precisely how many people died in the potato famine isn't merely an academic exercise. The demographic impact reshaped Ireland's social structure, influenced global migration patterns, and serves as a critical case study for modern food security experts.

Contemporary researchers at the University of Galway continue to study the famine's long-term effects, noting that "the population decline during the Great Hunger represents one of the most severe demographic shocks in modern European history." This research helps inform current approaches to famine prevention and humanitarian response.

Further Reading and Research

For those seeking additional verified information about Irish Potato Famine mortality statistics, these authoritative sources provide comprehensive data:

- National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park (Ireland)

- Irish Census Records 1821-1911 (National Archives of Ireland)

- "The Great Irish Famine" by Professor Cormac Ó Gráda (Cambridge University Press)

- Digital Repository of Ireland's Famine Collection

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4