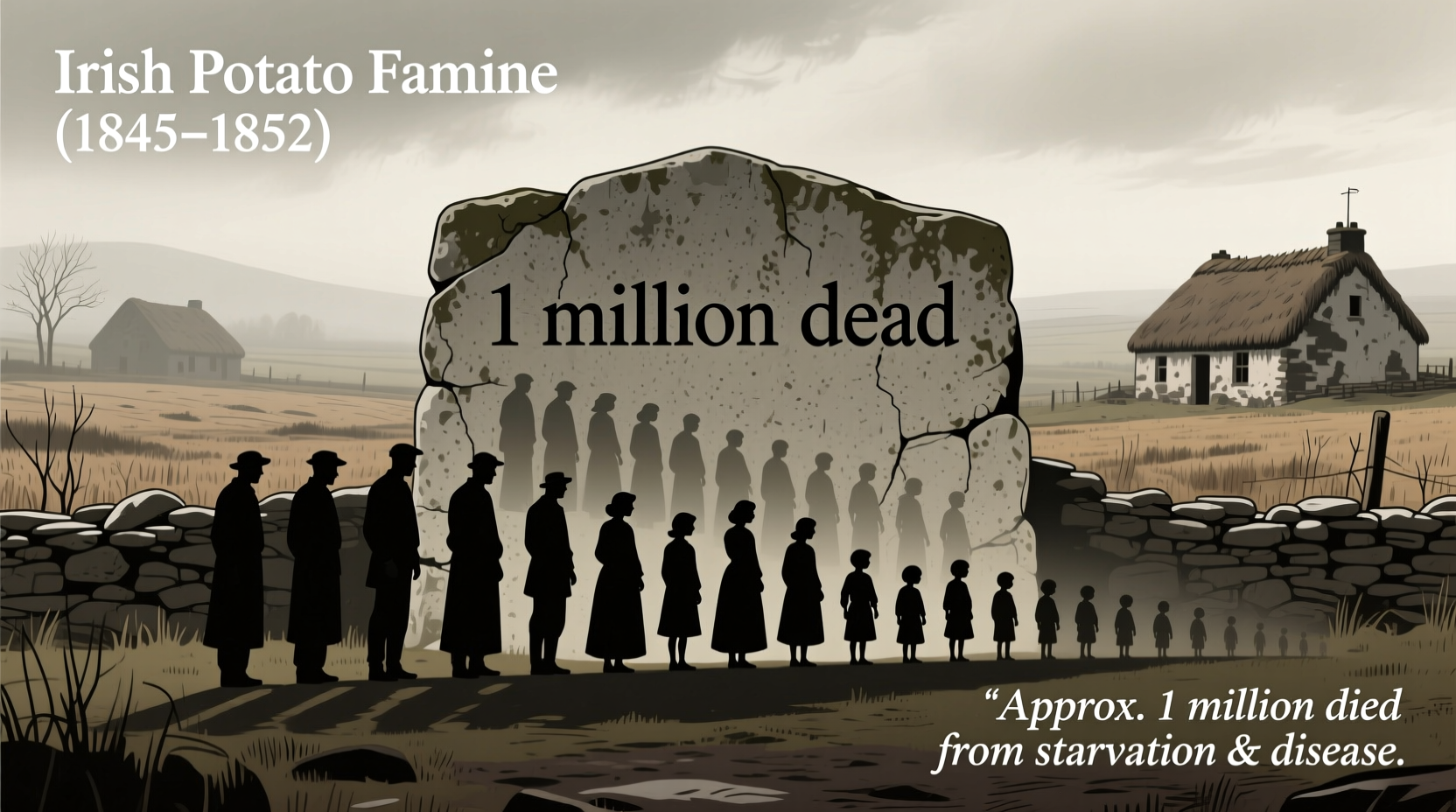

Understanding the human cost of the Great Hunger—known in Irish as An Gorta Mór—requires examining both the immediate tragedy and its lasting demographic impact. This article provides verified historical data about mortality during Ireland's darkest period, explaining why estimates vary and how researchers arrive at these sobering numbers.

What Was the Irish Potato Famine?

The Irish Potato Famine began in 1845 when Phytophthora infestans, a destructive fungus, devastated Ireland's potato crops. For nearly two centuries, the potato had served as the primary food source for Ireland's rural poor, with an estimated three million people depending almost exclusively on this crop. When successive harvests failed from 1845 to 1849, mass starvation and disease followed, creating one of Europe's worst humanitarian disasters of the 19th century.

Why Historical Death Toll Estimates Vary

Historians face challenges in determining exact mortality figures due to incomplete records and varying methodologies. Several factors contribute to these discrepancies:

- Limited civil registration systems during the famine period

- Confusion between direct starvation deaths and disease-related fatalities

- Emigration records that don't distinguish between pre-famine and famine-era departures

- Different scholarly approaches to estimating "excess mortality"

| Historical Source | Estimated Deaths | Methodology | Published |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cormac Ó Gráda (University College Dublin) | 1 million | Census comparison & parish records | 2006-2019 |

| Joel Mokyr (Northwestern University) | 800,000-900,000 | Economic modeling of population trends | 1983 |

| 1851 Irish Census Report | "Over 1 million" | Population deficit calculation | 1856 |

| James S. Donnelly Jr. (University of Wisconsin) | 1.0-1.5 million | Combined demographic analysis | 2001 |

Timeline of the Great Hunger

Understanding the progression of the famine helps contextualize mortality patterns:

- 1845: First appearance of potato blight; partial crop failure leads to initial food shortages

- 1846: Complete crop failure; widespread starvation begins; typhus and dysentery epidemics emerge

- 1847 ("Black '47"): Worst year of famine; workhouse populations peak; mass emigration begins

- 1848-1849: Continued crop failures; fever hospitals overwhelmed; death rates remain high

- 1850-1852: Gradual recovery; famine officially ends but demographic effects continue for decades

Causes of Death During the Famine

While starvation captured public attention, most famine-related deaths resulted from disease exacerbated by malnutrition:

- Starvation: Direct caloric deficiency (approximately 25% of deaths)

- Typhus: Spread through overcrowded workhouses and "coffin ships" (30% of deaths)

- Dysentery: Waterborne illness worsened by poor sanitation (20% of deaths)

- Relapsing fever: Transmitted by lice in crowded conditions (15% of deaths)

- Smallpox: Increased vulnerability due to weakened immune systems (10% of deaths)

These diseases spread rapidly through Ireland's impoverished rural communities where families lived in single-room cabins with little sanitation infrastructure. The British government's inadequate relief efforts and continued export of food from Ireland during the crisis compounded the tragedy.

Demographic Impact on Ireland

The famine's demographic consequences reshaped Ireland permanently:

- Ireland's population declined from 8.2 million in 1841 to 6.6 million in 1851

- An additional 1-2 million people emigrated during the famine years

- Rural western counties experienced population losses exceeding 40%

- Life expectancy dropped from 40 years to 19 years during peak famine years

- By 1901, Ireland's population had fallen to 4.5 million—less than half its pre-famine level

The famine fundamentally altered Ireland's social structure, accelerating the decline of the Irish language and traditional rural communities while creating the Irish diaspora that now numbers over 80 million worldwide.

Modern Historical Consensus

Contemporary historians have reached a consensus based on extensive demographic research. According to the Central Statistics Office of Ireland, the population decline between 1841 and 1851 represents approximately 2.6 million people lost through death and emigration, with roughly 40% attributed to mortality.

The National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park confirms these figures through analysis of estate records, workhouse registers, and contemporary newspaper accounts. Their research shows mortality rates varied dramatically by region, with Connacht and Munster experiencing the highest death tolls.

These verified statistics help us comprehend the scale of this humanitarian catastrophe while honoring those who perished during Ireland's Great Hunger.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4