Understanding potato chromosome count isn't just academic trivia—it directly impacts breeding programs, disease resistance, and the development of new potato varieties that feed millions worldwide. Whether you're a home gardener selecting varieties or a student researching plant genetics, this fundamental genetic information provides crucial context for understanding one of the world's most important food crops.

Decoding Potato Genetics: Beyond the Basic Count

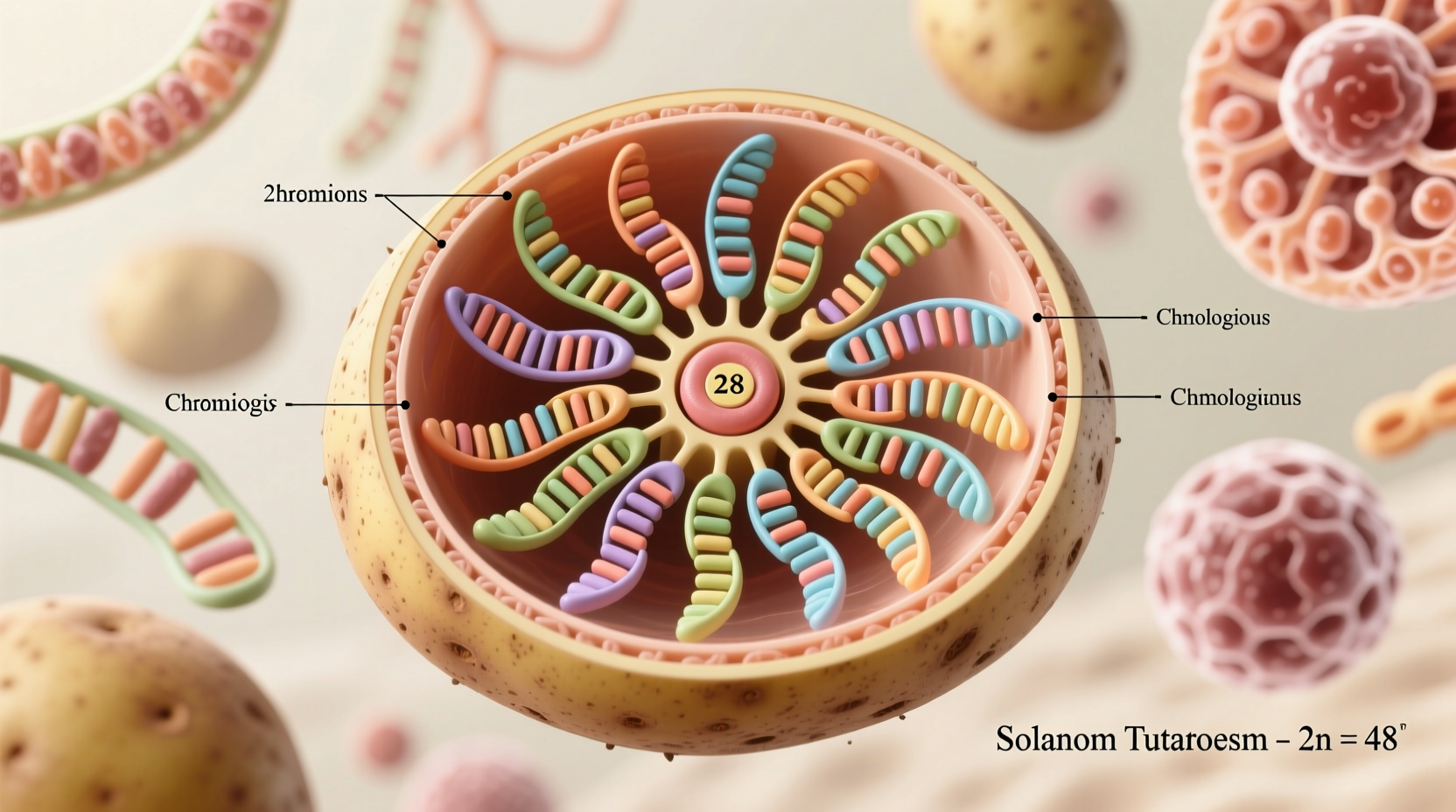

While the straightforward answer is 48 chromosomes for the common cultivated potato, the reality of potato genetics is more nuanced. Potatoes belong to the Solanum genus, which contains over 100 species with varying chromosome numbers. The cultivated potato we commonly eat (Solanum tuberosum subsp. tuberosum) maintains this tetraploid structure (four sets of chromosomes), but wild potato relatives show remarkable diversity in their genetic architecture.

Plant geneticists categorize potatoes by their ploidy level—the number of complete sets of chromosomes:

| Ploidy Level | Chromosome Count | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| Diploid | 24 (2n=2x=24) | Many wild potato species |

| Triploid | 36 (2n=3x=36) | Rare cultivated varieties |

| Tetraploid | 48 (2n=4x=48) | Most cultivated potatoes (99% of commercial varieties) |

| Pentaploid | 60 (2n=5x=60) | Some Andean landraces |

| Hexaploid | 72 (2n=6x=72) | Very rare cultivars |

Why Chromosome Count Matters in Potato Breeding

The tetraploid nature of cultivated potatoes creates unique challenges for plant breeders. Unlike diploid organisms (including humans) that inherit one set of chromosomes from each parent, tetraploid potatoes inherit four sets—two from each parent plant. This complex inheritance pattern makes trait selection more difficult but also provides greater genetic diversity.

When the International Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium completed the potato genome project in 2011, they confirmed the 48-chromosome structure and identified approximately 39,000 genes. This breakthrough has accelerated breeding programs focused on:

- Developing varieties resistant to late blight (the pathogen behind the Irish Potato Famine)

- Creating potatoes with enhanced nutritional profiles

- Engineering drought-tolerant varieties for changing climate conditions

- Reducing acrylamide formation during frying (a potential carcinogen)

Evolutionary Timeline of Potato Genetics Research

Understanding potato chromosome count didn't happen overnight. Here's how scientific knowledge has evolved:

- 1920s: First chromosome counts identify cultivated potatoes as tetraploid (48 chromosomes)

- 1940s-1950s: Development of haploid techniques to simplify potato genetics research

- 1970s: Creation of the first genetically modified potato plants

- 1990s: Molecular marker development accelerates breeding programs

- 2011: Complete sequencing of the potato genome confirms chromosome structure

- 2020s: CRISPR gene editing applied to develop improved potato varieties

This progression shows how fundamental chromosome knowledge enables advanced genetic research. According to research published in Nature Genetics, modern sequencing has revealed that potato chromosomes contain numerous repetitive sequences that complicate genetic analysis but also provide evolutionary advantages.

Practical Implications for Gardeners and Farmers

While chromosome count might seem abstract, it directly affects agricultural practices:

- Seed saving limitations: Potatoes rarely produce true seeds that maintain desirable traits due to their tetraploid genetics—this is why farmers plant tubers rather than seeds

- Cross-breeding challenges: Creating new varieties requires careful selection due to complex inheritance patterns

- Disease resistance: The multiple chromosome sets provide genetic redundancy that helps potatoes withstand certain pathogens

- Climate adaptation: Genetic diversity across chromosome sets allows for selection of climate-resilient traits

For home gardeners, understanding that potatoes are tetraploid explains why saving seeds from potato fruits rarely produces plants identical to the parent. The International Potato Center (CIP) in Peru maintains over 7,000 potato varieties, leveraging this genetic complexity to preserve traits that might prove vital as climate conditions change.

Comparative Chromosome Analysis Across Common Crops

Placing potato chromosomes in context with other staple crops reveals interesting evolutionary patterns:

| Plant Species | Common Name | Chromosome Count | Ploidy Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solanum tuberosum | Cultivated Potato | 48 | Tetraploid |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Tomato | 24 | Diploid |

| Zea mays | Corn | 20 | Diploid |

| Triticum aestivum | Bread Wheat | 42 | Hexaploid |

| Oryza sativa | Rice | 24 | Diploid |

| Solanum phureja | Wild Potato | 24 | Diploid |

This comparison shows how potatoes sit in an intermediate genetic complexity range among major food crops. While wheat has evolved to a higher ploidy level (hexaploid), potatoes maintain their tetraploid structure that balances genetic diversity with breeding feasibility.

Common Misconceptions About Potato Chromosomes

Several misunderstandings persist about potato genetics:

- Misconception: All potatoes have exactly the same chromosome structure

Reality: While cultivated varieties are predominantly tetraploid (48 chromosomes), wild relatives range from diploid (24) to hexaploid (72) - Misconception: Chromosome count determines potato size or yield

Reality: These traits are influenced by specific genes across the chromosomes, not the total count - Misconception: Genetically modified potatoes have different chromosome numbers

Reality: Genetic modification typically alters specific genes without changing overall chromosome count

According to agricultural researchers at Cornell University, understanding these distinctions helps farmers make informed decisions about variety selection and breeding approaches.

Future Research Directions in Potato Genetics

Current research focuses on leveraging our understanding of potato chromosomes to address global food security challenges. Scientists are exploring:

- Developing diploid potato breeding lines to simplify genetics while maintaining desirable traits

- Mapping specific genes on potato chromosomes responsible for disease resistance

- Understanding epigenetic factors that affect gene expression without altering chromosome structure

- Creating chromosome-level assemblies for diverse potato varieties to capture full genetic diversity

The USDA Agricultural Research Service notes that precise knowledge of potato chromosome organization has already contributed to varieties with 30% greater resistance to late blight, potentially saving billions in crop losses annually.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all potato varieties have the same number of chromosomes?

No, while 99% of commercial potato varieties are tetraploid with 48 chromosomes, wild potato species can be diploid (24 chromosomes), triploid (36), pentaploid (60), or hexaploid (72). Some traditional Andean varieties also show different ploidy levels.

Why do potatoes have more chromosomes than humans?

Chromosome count doesn't correlate with organism complexity. Humans have 46 chromosomes (diploid), while potatoes have 48 (tetraploid). Many plants have higher chromosome counts due to evolutionary polyploidy events where entire genome sets duplicate, providing genetic flexibility for environmental adaptation.

How was the potato chromosome count determined?

Scientists determine chromosome counts through karyotyping—staining and photographing chromosomes during cell division (mitosis). The first accurate counts for potatoes were made in the 1920s using microscopic examination of root tip cells, and modern techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) now provide even more detailed chromosome mapping.

Does chromosome count affect potato nutrition?

The chromosome count itself doesn't directly determine nutrition, but the genes carried on those chromosomes do. Different potato varieties (with the same 48 chromosomes) can have significant nutritional differences. For example, purple potatoes contain anthocyanin genes on specific chromosomes that provide antioxidant benefits not found in white-fleshed varieties.

Can chromosome count change in potatoes?

Natural chromosome count changes (ploidy shifts) are rare but possible through spontaneous mutations. Plant breeders can intentionally create different ploidy levels using chemicals like colchicine. Most commercial potatoes maintain stable tetraploid (48 chromosome) structure across generations due to selective breeding for desirable traits.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4