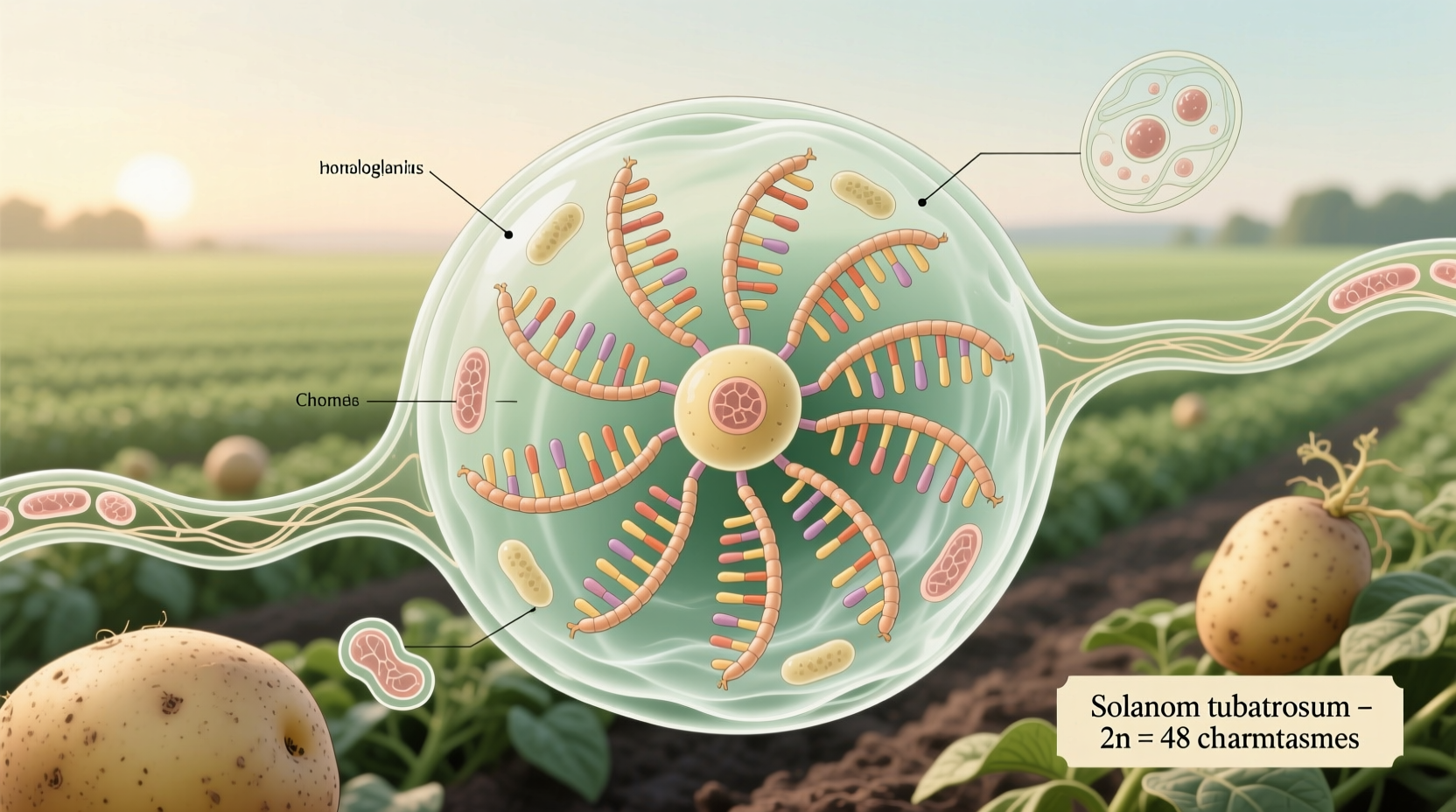

The common cultivated potato (Solanum tuberosum) has 48 chromosomes, organized as a tetraploid species with four sets of 12 chromosomes (2n=4x=48). This specific chromosome count is fundamental to potato breeding, cultivation, and genetic research worldwide.

Understanding potato genetics isn't just academic curiosity—it directly impacts crop resilience, disease resistance, and yield potential for farmers and gardeners. Whether you're a student researching plant biology, a home gardener planning your next crop rotation, or a professional breeder developing new varieties, knowing the chromosomal structure of potatoes provides essential context for successful cultivation.

Why Potato Chromosome Count Matters to Growers

Unlike many common vegetables, potatoes possess a complex tetraploid genome that affects everything from disease resistance to tuber quality. The 48-chromosome structure (compared to diploid species with just two sets) creates unique breeding challenges but also offers greater genetic diversity. This complexity explains why developing new potato varieties takes significantly longer than with simpler crops.

When you understand that cultivated potatoes carry four copies of each chromosome rather than the typical two found in most organisms, you gain insight into why certain traits manifest differently in potato breeding programs. This knowledge helps explain inconsistent results when crossing varieties and informs better selection practices for home gardeners saving their own seed potatoes.

Chromosome Variation Across Potato Species

While Solanum tuberosum (the common potato) has 48 chromosomes, the potato family tree reveals fascinating genetic diversity:

| Species Type | Chromosome Count | Ploidy Level | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated Potato (S. tuberosum) | 48 | Tetraploid (4x) | Commercial varieties worldwide |

| Wild Potato (S. chacoense) | 24 | Diploid (2x) | Source of disease resistance genes |

| Wild Potato (S. acaule) | 48 | Tetraploid (4x) | Cold tolerance traits |

| Wild Potato (S. demissum) | 60 | Pentaploid (5x) | Source of late blight resistance |

This variation explains why plant breeders often cross cultivated potatoes with wild relatives—they're accessing valuable genetic traits while navigating complex chromosome pairing during meiosis. The USDA Agricultural Research Service maintains extensive potato germplasm collections specifically to preserve this genetic diversity for future breeding efforts (USDA ARS).

Historical Development of Potato Genetics Research

The journey to understanding potato chromosomes spans nearly a century of scientific advancement:

- 1920s-1930s: Early cytologists first identified potato's tetraploid nature through microscopic examination of cell division

- 1940s-1950s: Researchers established the basic chromosome number (2n=48) and began mapping visible traits

- 1970s-1980s: Development of somatic hybridization techniques allowed chromosome manipulation between species

- 2000s-Present: Complete potato genome sequencing revealed detailed gene locations across all 12 chromosome types

This timeline reflects how technological advances transformed our understanding from basic chromosome counting to precise gene mapping. The International Potato Center (CIP) in Peru has been instrumental in documenting wild potato species' genetic diversity since its founding in 1971, preserving over 7,000 potato accessions for research (CIP).

Practical Implications for Modern Agriculture

Knowing that potatoes have 48 chromosomes isn't merely academic—it directly impacts farming practices. Tetraploid genetics create unique challenges in breeding programs where trait inheritance follows more complex patterns than in diploid crops. This explains why developing a new disease-resistant variety typically takes 10-15 years compared to 5-7 years for many diploid crops.

For home gardeners, understanding potato ploidy helps explain why saving seed from hybrid varieties rarely produces consistent results. The multiple chromosome sets create greater genetic variation in offspring, making tuber propagation (rather than true seed) the preferred method for maintaining specific characteristics.

Modern genomic selection techniques now allow breeders to screen young plants for desirable traits without waiting for full maturity—significantly accelerating variety development. This technology builds directly on our understanding of potato chromosome structure and organization.

Common Misconceptions About Potato Genetics

Many gardeners mistakenly believe all potatoes share identical genetic structures. In reality, different cultivars show significant variation within the tetraploid framework. Some modern breeding programs are even developing diploid potatoes (with 24 chromosomes) to simplify genetics while maintaining desirable traits.

Another frequent error involves confusing chromosome count with genome size. While potatoes have 48 chromosomes, their total DNA content (approximately 840 million base pairs) is actually smaller than tomatoes (which have just 24 chromosomes but more DNA per chromosome). This distinction matters when considering genetic complexity beyond simple chromosome counts.

How Researchers Study Potato Chromosomes Today

Modern cytogenetic techniques have revolutionized our understanding of potato chromosome behavior. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) allows researchers to visualize specific DNA sequences on individual chromosomes, while genomic in situ hybridization (GISH) helps track chromosome movement during hybridization.

At Cornell University's Boyce Thompson Institute, scientists use these advanced techniques to develop chromosome substitution lines—replacing specific potato chromosomes with those from wild relatives to introduce valuable traits like pest resistance without undesirable characteristics (BTI).

These sophisticated approaches build upon the fundamental knowledge that cultivated potatoes possess 48 chromosomes organized as four sets of 12 distinct types. This chromosomal architecture remains the foundation for all modern potato improvement efforts.

Looking Forward: Chromosome Engineering in Potato Breeding

Emerging technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing are transforming potato breeding by allowing precise modifications within the complex tetraploid genome. Researchers can now target specific genes on particular chromosomes without introducing foreign DNA—a significant advantage over traditional genetic modification approaches.

The Solanaceae Genomics Network maintains detailed chromosome maps that help researchers navigate the potato genome's complexity (SGN). These resources accelerate the development of improved varieties with enhanced nutritional content, climate resilience, and disease resistance—all building upon our fundamental understanding of potato chromosome structure.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all potato varieties have the same number of chromosomes?

Most cultivated potato varieties (Solanum tuberosum) have 48 chromosomes as tetraploids, but wild potato species show significant variation ranging from 24 to 60 chromosomes depending on ploidy level. Some modern breeding programs are developing diploid potatoes with 24 chromosomes to simplify genetics.

Why do potatoes have more chromosomes than humans?

Chromosome count doesn't correlate with organism complexity. Potatoes evolved as tetraploids (4x=48) through natural genome duplication events, while humans remained diploid (2x=46). Many plants have higher chromosome counts than animals due to polyploidy events during evolution.

How does potato chromosome count affect breeding?

The tetraploid nature (48 chromosomes) creates complex inheritance patterns as each parent contributes four copies of each chromosome rather than two. This makes trait selection more challenging but also provides greater genetic diversity. Breeders use specialized techniques like double haploid production to simplify genetic analysis.

Can chromosome count help identify potato species?

Yes, chromosome count is a key taxonomic characteristic. While cultivated potatoes have 48 chromosomes, wild relatives may have 24 (diploid), 36 (triploid), 48 (tetraploid), or 60 (pentaploid) chromosomes. Cytogenetic analysis combined with morphological traits helps scientists accurately classify potato species.

How was the potato chromosome count first discovered?

Early cytologists in the 1920s-1930s first identified potato's chromosome count through microscopic examination of root tip cells during mitosis. Researchers like J.E. Lindley and later G.A. de Wet published detailed cytological studies confirming the tetraploid nature (2n=4x=48) of cultivated potatoes.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4