Why You Won't Find True Fossilized Potatoes in Nature

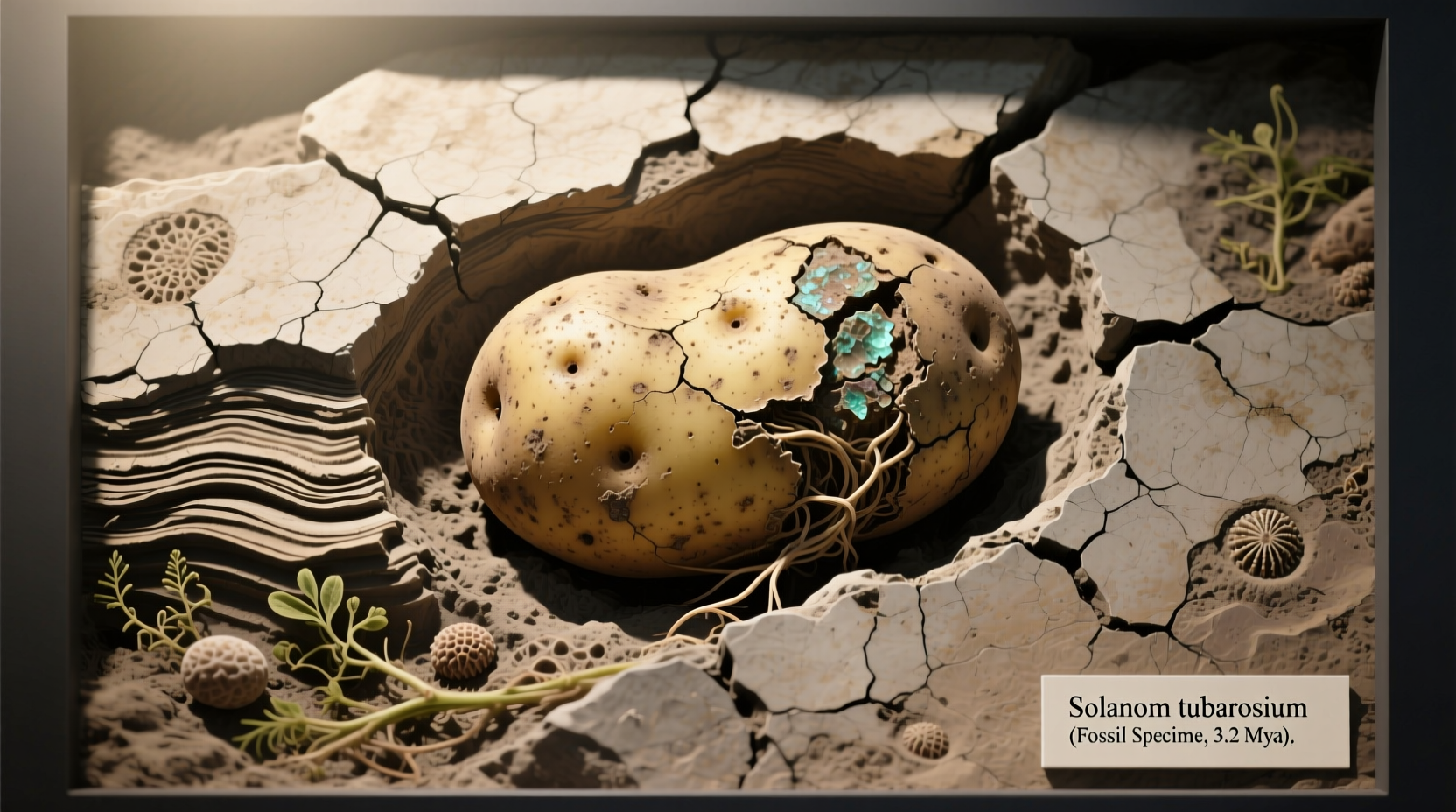

When you search for “fossilized potato,” you're likely encountering misleading terminology. True fossilization requires mineral replacement of organic material over millions of years — a process incompatible with potato tubers' biological structure. Potatoes decompose within weeks under normal conditions, making genuine fossilization impossible. Instead, archaeologists identify ancient potato evidence through starch grains, phytoliths, and cultivation imprints.

The Science Behind Plant Fossilization vs. Potato Preservation

Understanding why potatoes don't fossilize requires examining the fossilization process:

| Process | Requirements | Applies to Potatoes? |

|---|---|---|

| Permineralization | Mineral-rich water saturation, millions of years | No – tubers decay too quickly |

| Carbonization | Pressure transforming organic matter to carbon film | Rarely – only in exceptional preservation conditions |

| Mold/Cast formation | Organism decaying then mineral filling space | No – potatoes lack rigid structure for molds |

| Actual remains | Freezing, drying, or chemical preservation | Yes – archaeological specimens, not fossils |

What Researchers Actually Study: Ancient Potato Evidence

While true fossilized potatoes don't exist, scientists have documented potato cultivation dating back 8,000 years through alternative evidence:

- Starch grain analysis: Microscopic potato starch residues found on ancient tools in Peru (University of Oxford, 2018)

- Phytoliths: Silica structures from potato plant tissues preserved in soil layers (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2020)

- Ceramic impressions: Potato shapes preserved in ancient pottery from the Andes

- Desiccated remains: Naturally dried potato specimens from arid cave environments

Timeline of Potato Domestication Evidence

Archaeological discoveries reveal potato's journey from wild tuber to global staple:

- 8000 BCE: Earliest evidence of potato cultivation in southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia

- 2000 BCE: Potato remains found in coastal Peruvian archaeological sites

- 1537: Spanish explorers document potato cultivation in Colombia

- 1570: First European potato cultivation records in Spain

- 1949: Discovery of 2,300-year-old potato remains in Chile's Casma Valley

- 2010: Genetic analysis confirms multiple domestication events across South America

Common Misconceptions About “Fossilized Potatoes”

Several factors contribute to the confusion around “fossilized potatoes”:

- Marketing terminology: Some agricultural products use “fossilized” to describe ancient mineral deposits used as fertilizer

- Metaphorical usage: Chefs sometimes call overcooked potatoes “fossilized” as hyperbole

- Misidentified specimens: Petrified wood or other plant fossils occasionally mistaken for potato remains

- Preservation confusion: Desiccated archaeological specimens preserved in dry caves mistaken for fossils

Practical Implications for Gardeners and Historians

Understanding the distinction between fossilization and preservation helps avoid historical inaccuracies:

- When researching ancient agriculture, search for “archaeobotanical potato evidence” rather than “fossilized potatoes”

- Preserve heirloom potato varieties to maintain genetic diversity lost in commercial cultivation

- Recognize that potato's rapid decomposition explains why direct tuber evidence is rare in archaeological sites

- Understand that modern potatoes differ significantly from their wild ancestors through selective breeding

Where to Find Authentic Ancient Potato Research

For accurate information about potato history, consult these authoritative sources:

- The International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru maintains the world's largest potato genetic collection

- Peer-reviewed journals like Economic Botany and Journal of Archaeological Science

- University archaeobotany departments such as University College London's Institute of Archaeology

- Museum collections like the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History's archaeobotanical archive

Frequently Asked Questions

Can potatoes actually become fossils?

No, potatoes cannot become true fossils. Their high water content and soft tissue structure cause rapid decomposition, preventing the mineralization process required for fossilization. What's sometimes called “fossilized potato” is typically preserved archaeological material, not a geological fossil.

What's the oldest potato evidence ever discovered?

The oldest direct evidence comes from 8,000-year-old starch grains found at archaeological sites in southern Peru. Researchers from the University of Oxford identified these microscopic residues on ancient grinding stones, confirming early potato cultivation.

How do scientists study ancient potatoes if they don't fossilize?

Scientists use alternative methods including starch grain analysis, phytolith identification, examination of ceramic impressions, and genetic studies of modern potato varieties. In rare cases, desiccated potato specimens preserved in extremely dry cave environments provide direct evidence.

Why do some products claim to contain “fossilized potatoes”?

This is typically marketing terminology misapplied to ancient mineral deposits like Leonardite, which formed from decomposed plant matter millions of years ago. These products contain no actual potato material — the term refers to the geological origin of the minerals, not preserved potato specimens.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4