Despite common labeling in U.S. grocery stores, sweet potatoes and yams are completely different root vegetables. True yams (Dioscorea species) originate from Africa and Asia, have rough bark-like skin, and are rarely found in American supermarkets. What's labeled as “yam” in the U.S. is almost always an orange-fleshed sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), native to Central and South America. The confusion began when orange-fleshed sweet potatoes were introduced to distinguish them from traditional white-fleshed varieties.

Why You've Been Misled Your Entire Life

Walk into any American grocery store and you'll likely see “yams” prominently displayed next to sweet potatoes during holiday seasons. Here's the shocking truth: 99% of products labeled “yams” in U.S. stores are actually sweet potatoes. This widespread mislabeling dates back to the early 20th century when orange-fleshed sweet potatoes entered the market and distributors needed to distinguish them from the traditional white-fleshed varieties already popular in the South.

Botanical Breakdown: Not Even Distant Cousins

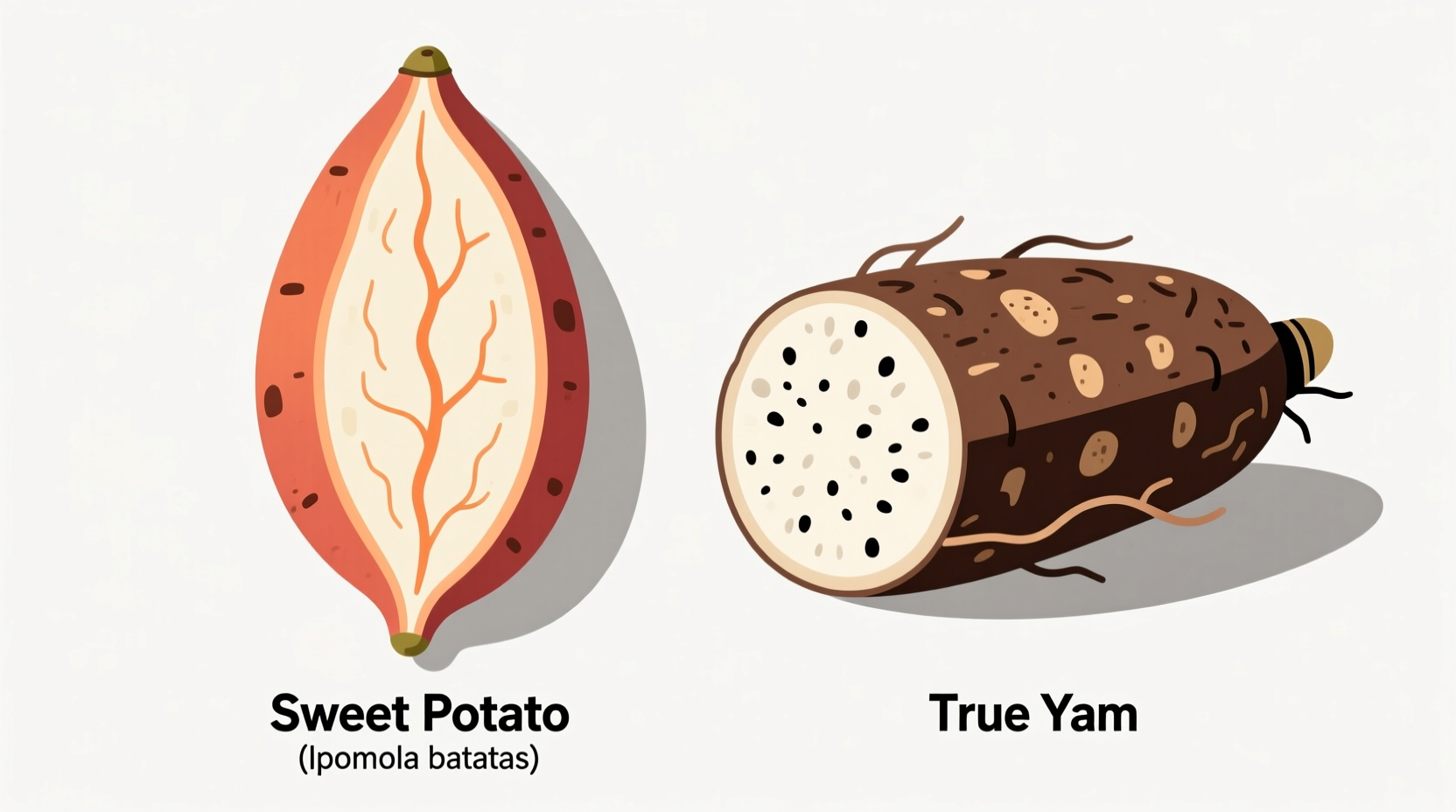

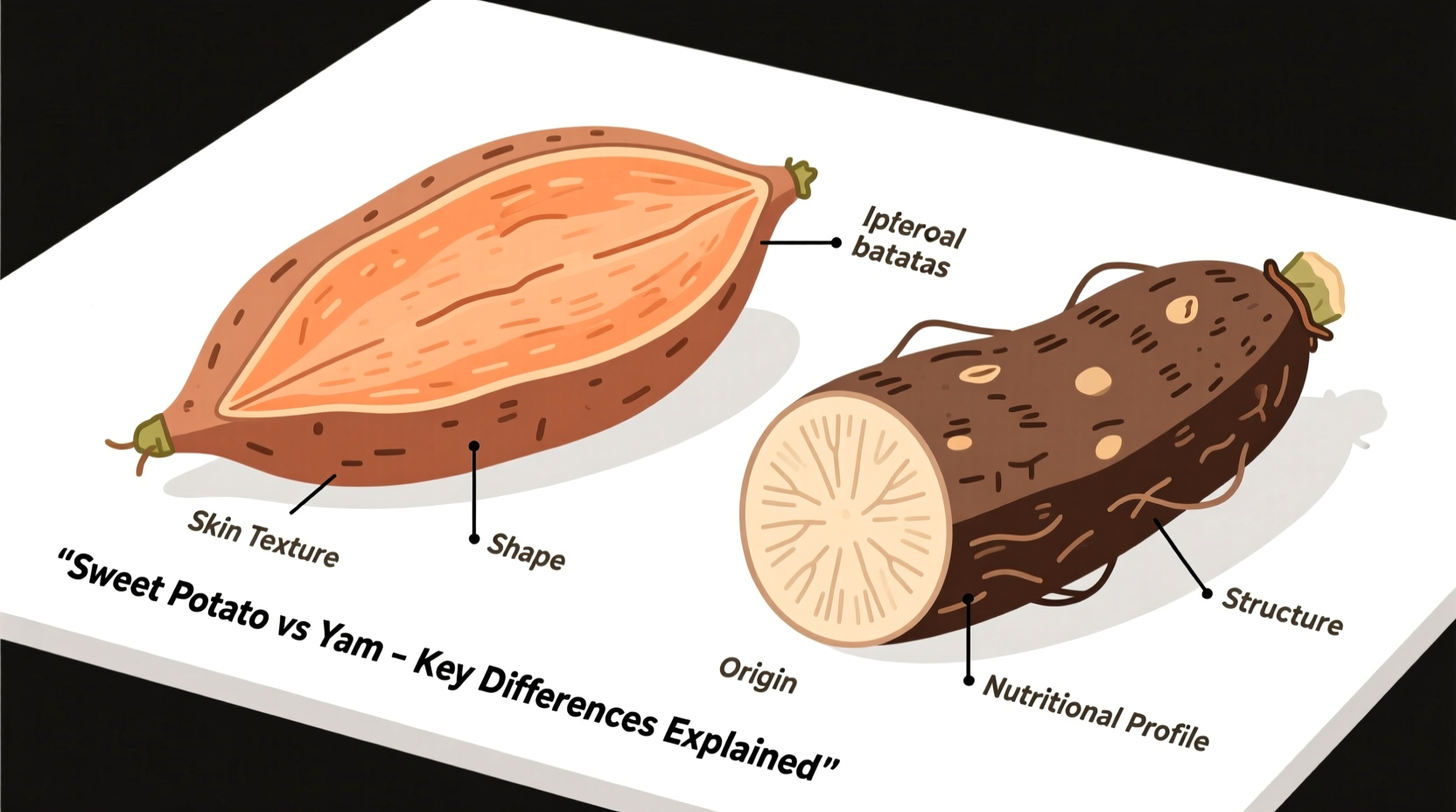

Sweet potatoes and yams belong to entirely different plant families with no botanical relationship:

| Characteristic | Sweet Potato | True Yam |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Classification | Ipomoea batatas (morning glory family) | Dioscorea species (yam family) |

| Native Region | Central/South America | West Africa, Asia |

| Texture | Moist, tender when cooked | Dry, starchy, sometimes fibrous |

| Vitamin A Content | Extremely high (orange varieties) | Very low |

| Shelf Life | 2-3 weeks | 6-12 months |

The Historical Mix-Up Timeline

The confusion didn't happen by accident. Here's how sweet potatoes became masquerading as yams in America:

- Pre-1930s: White and yellow-fleshed sweet potatoes dominated U.S. markets

- 1930s: Louisiana farmers introduced orange-fleshed varieties from Central America

- Marketing Strategy: To distinguish the new orange varieties, marketers borrowed “yam” from the African word “nyami” (meaning “to eat”)

- USDA Regulation (1930s): Required that any product labeled “yam” must also include “sweet potato”

- Present Day: Most retailers ignore the dual-labeling requirement, perpetuating the confusion

Nutritional Showdown: What Your Body Actually Gets

Understanding the nutritional differences matters for your health decisions. According to USDA FoodData Central, a medium sweet potato (130g) provides:

- 438% of your daily vitamin A needs (as beta-carotene)

- 37% of vitamin C

- 28% of manganese

- 150 calories, 5g fiber

Meanwhile, true yams contain significantly less vitamin A but more potassium and resistant starch. The orange color in sweet potatoes comes from beta-carotene, which true yams lack entirely. This nutritional distinction explains why orange sweet potatoes are recommended for vitamin A deficiency prevention programs in developing countries, as documented by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Shopping Smart: How to Identify What You're Buying

Follow these practical steps to ensure you're getting what you think you're buying:

- Read labels carefully: Look for “sweet potato” in small print beneath “yam”

- Examine the skin: True yams have rough, bark-like skin; sweet potatoes have smoother skin

- Check the shape: Yams are usually longer and cylindrical; sweet potatoes are tapered

- Ask store staff: Specialty markets sometimes carry actual yams, particularly Caribbean or African grocers

- Consider the season: True yams aren't seasonal in the U.S. - if it's only available during holidays, it's definitely a sweet potato

Culinary Applications: Why the Difference Matters in Your Kitchen

The confusion isn't just academic—it affects your cooking results. Sweet potatoes' higher sugar content and moisture make them ideal for roasting, mashing, and baking into desserts. Their natural sweetness caramelizes beautifully. True yams, with their starchier composition, behave more like potatoes and work better in soups, stews, and fried preparations where maintaining structure is important.

Chef Thomas Keller notes in Ad Hoc at Home that understanding this distinction prevents recipe failures: “Using what you think is a yam but is actually a sweet potato can throw off moisture ratios in savory dishes, while substituting a true yam in a sweet potato pie recipe will result in a dense, flavorless disaster.”

Global Perspective: How Different Cultures Use These Roots

Outside the U.S., the distinction remains clear. In West Africa, yams (called “ji” in Yoruba) are cultural staples central to harvest festivals. The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture reports that Nigeria produces over 70 million tons of true yams annually—more than the rest of the world combined. Meanwhile, sweet potatoes have become Japan's most popular root vegetable, with purple varieties like beni imo prized for their antioxidants.

The confusion is almost exclusively an American phenomenon. As the USDA Agricultural Research Service explains, “the misnomer persists due to historical marketing practices rather than botanical accuracy.”

Practical Takeaways for Everyday Cooking

Here's how to apply this knowledge immediately:

- For Thanksgiving casseroles: Use orange-fleshed “yams” (actually sweet potatoes) for that classic sweet, moist texture

- For authentic African dishes: Seek true yams at Caribbean markets—they're essential for fufu and other traditional preparations

- For maximum nutrition: Choose orange sweet potatoes for vitamin A, purple varieties for antioxidants

- When substituting: Remember that true yams require longer cooking times than sweet potatoes

- For food safety: Never eat raw yams—many varieties contain toxic compounds destroyed by proper cooking

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4