Have you ever searched for 'banana potato' wondering if it's a real food item? You're not alone. This frequent search query reveals a widespread confusion between plantains (often called 'cooking bananas') and actual potatoes. As a culinary specialist with extensive experience in Latin American ingredients, I've seen this misunderstanding countless times in markets and kitchens. Let's clarify this confusion once and for all and provide practical guidance for your cooking adventures.

Understanding the Botanical Reality

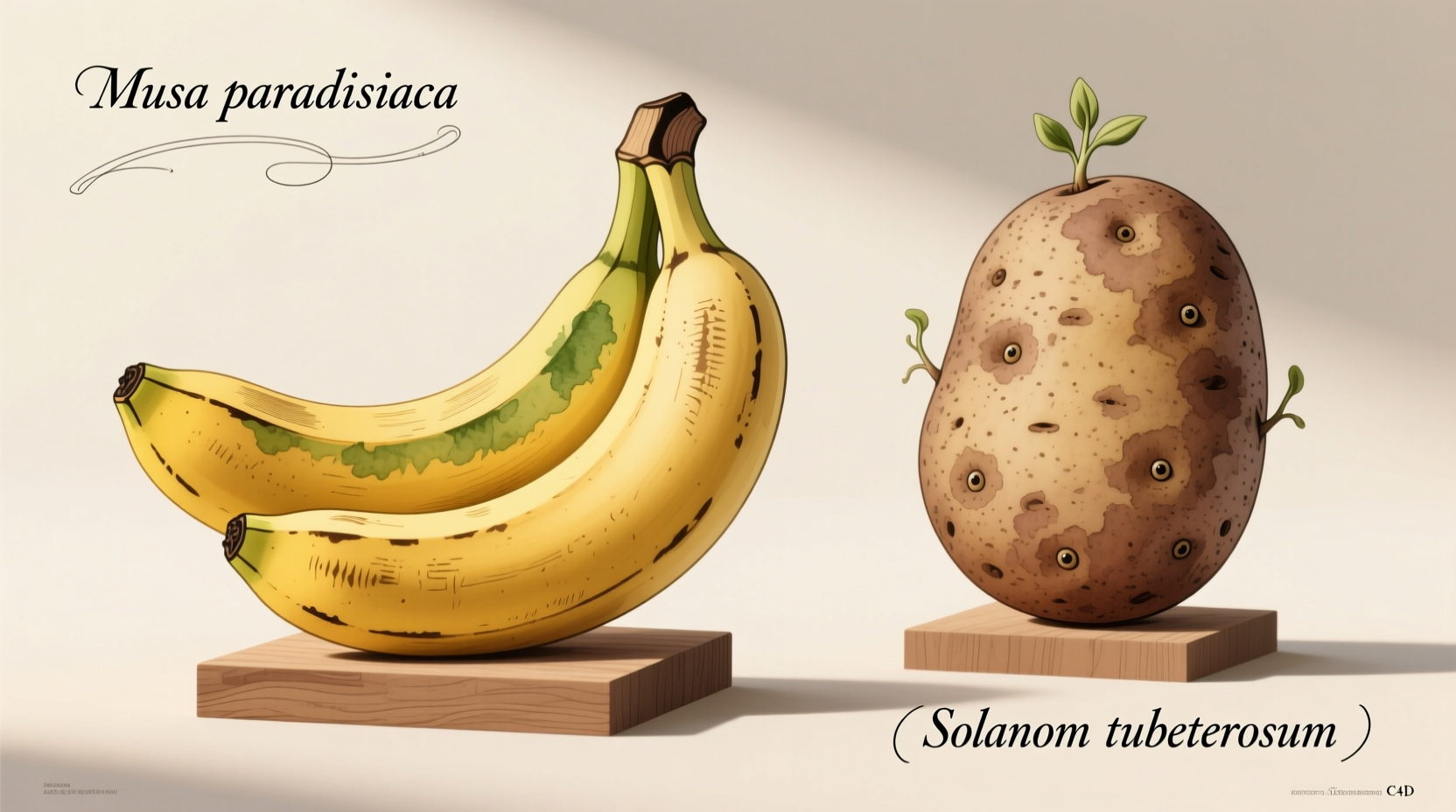

Despite the confusing terminology, banana potatoes don't exist as a single food item. What people often mean are either:

- Plantains - Starchy members of the banana family (Musa genus) used in cooking

- Sweet potatoes - Sometimes confused due to regional naming differences

- Finger bananas - Small banana varieties that might resemble small potatoes

Plantains, frequently called "cooking bananas" or mistakenly referred to as "banana potatoes," are actually more closely related to dessert bananas than to potatoes. The confusion stems from their starchy texture and common use in savory dishes similar to potatoes.

| Characteristic | Plantains | Regular Bananas | Potatoes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botanical Family | Musa (banana family) | Musa (banana family) | Solanum (nightshade family) |

| Starch Content | High (70-80% when unripe) | Lower (converts to sugar as ripens) | Very high (15-20%) |

| Sugar Content | Low when green, increases as ripens | High (12-15%) | Moderate (0.5-1.5%) |

| Common Culinary Use | Savory dishes when green, sweet when ripe | Primarily eaten raw as fruit | Versatile in both savory and some sweet dishes |

| Storage Requirements | Room temperature, not refrigerated | Room temperature | Cool, dark place (not refrigerated) |

Why the Confusion Persists

The "banana potato" misconception has several roots. In many Latin American and Caribbean cultures, plantains are dietary staples prepared in ways similar to potatoes - fried, boiled, or mashed. The USDA notes that in some regions, the term "banana" is used broadly for all Musa varieties, including starchy plantains that function like potatoes in meals.

According to agricultural research from the University of Florida's Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, the confusion intensified when African and Caribbean immigrants brought plantain-based cuisines to North America, where the distinction between plantains and bananas wasn't widely understood.

When Substitutions Work (and When They Don't)

Understanding the practical differences between plantains and potatoes is crucial for successful cooking. While they share some culinary applications, they're not always interchangeable.

Successful Substitutions

- Green plantains for potatoes in frying: Both create excellent crispy textures when fried, making plantains a popular alternative for tostones (twice-fried plantains) instead of potato chips

- Mashed ripe plantains for sweet potato dishes: Their natural sweetness works well in desserts where you'd use sweet potatoes

- Boiled green plantains in stews: They hold their shape well in soups similar to potatoes

Where Substitutions Fail

- Baking: Plantains lack the structural properties of potatoes in baked goods

- Salads: Plantains become too soft when cooled, unlike waxy potatoes that maintain texture

- Recipes requiring neutral flavor: Plantains have a distinct banana-like flavor even when unripe

Regional Terminology Explained

The confusion is compounded by regional naming differences. In West Africa and the Caribbean, "cooking banana" commonly refers to plantains, while in the United States, many people mistakenly call them "banana potatoes."

According to linguistic research from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the term "yam" in American grocery stores typically refers to orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, adding another layer to the confusion. True yams (Dioscorea genus) are entirely different from both potatoes and plantains.

Practical Cooking Guidance

When working with these ingredients, consider these key practical differences:

- Ripeness matters: Plantains change dramatically from green (starchy) to yellow/black (sweet), while potatoes maintain consistent properties

- Cooking time varies: Green plantains often require longer cooking than potatoes to become tender

- Moisture content differs: Plantains contain more moisture, affecting recipes like mashed preparations

- Flavor pairing: Plantains pair well with tropical flavors (coconut, citrus) while potatoes complement earthy herbs

For best results, never substitute raw bananas for potatoes - their high sugar and low starch content will completely alter your dish. If you're looking for potato alternatives, green plantains are your best option, but expect subtle flavor differences.

Storage and Selection Tips

Proper storage significantly impacts usability:

- Plantains: Store at room temperature; refrigeration causes skin blackening (though the inside remains fine)

- Potatoes: Keep in cool, dark place; never refrigerate as cold temperatures convert starch to sugar

- Selection: Choose firm, blemish-free specimens; avoid soft spots or sprouting

When selecting plantains for savory applications, look for green skins; for sweeter dishes, choose yellow with black spots.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4