Why This Guide Matters for Gardeners and Cooks

Discover everything you need to know about cultivating and using Allium fistulosum effectively. This comprehensive resource delivers science-backed growing techniques, culinary applications across global cuisines, and practical storage solutions—all verified through agricultural research and culinary expertise. Whether you're planning your garden or elevating your cooking, you'll gain actionable knowledge to maximize this versatile ingredient's potential.

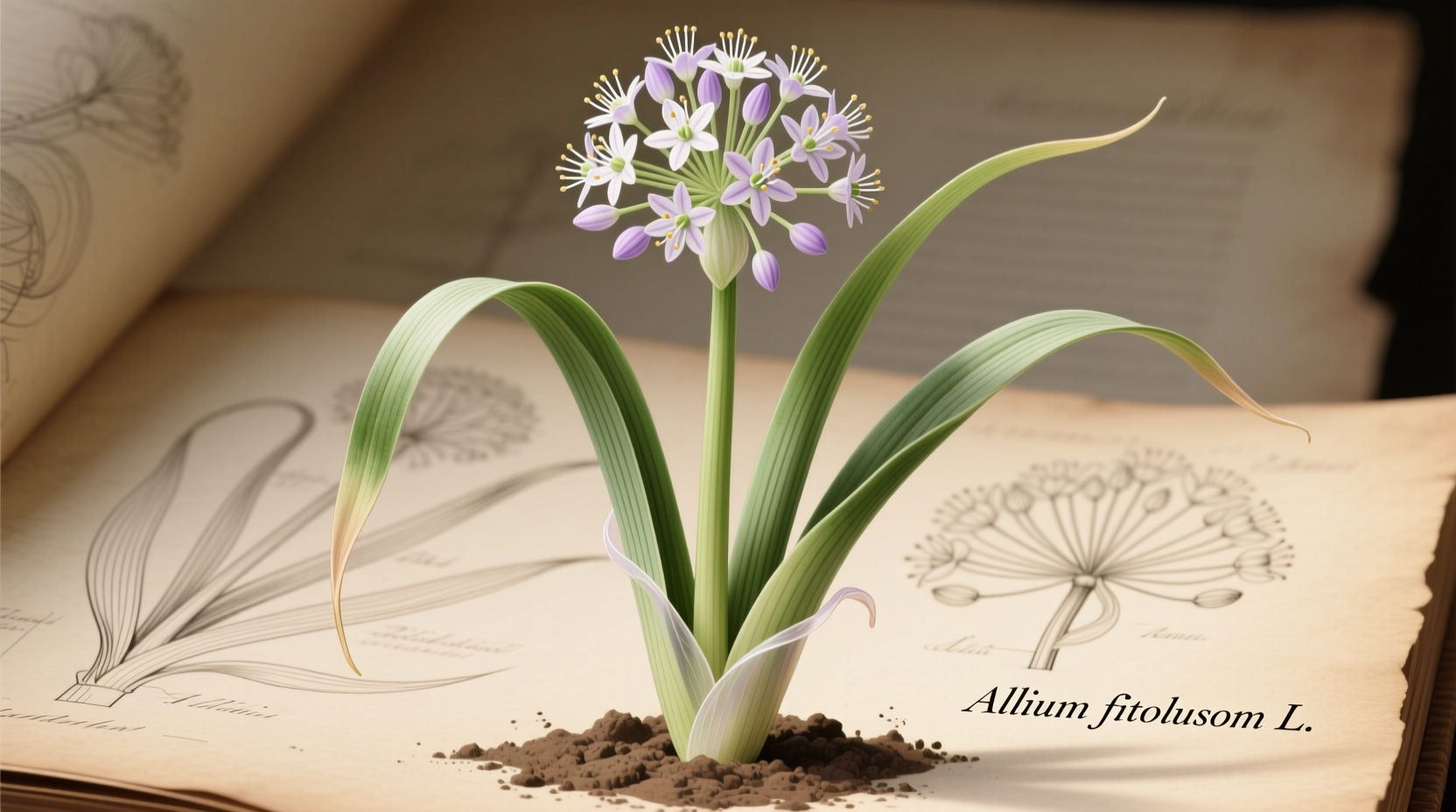

Clear Identification: What Makes Allium fistulosum Unique

Allium fistulosum stands apart from other allium varieties through distinctive physical characteristics. Its hollow, cylindrical green leaves grow from a small, fibrous root system without developing the large, layered bulbs typical of common onions. The plant maintains consistent diameter from base to tip, with white lower sections that never swell into substantial bulbs. This perennial species regrows annually from its base, making it ideal for continuous harvesting.

Despite its misleading "Welsh" designation (derived from the German "welsch" meaning "foreign"), this plant has ancient roots in Chinese agriculture. Historical records from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) document its cultivation, with archaeological evidence suggesting domestication began over 3,000 years ago in the Shandong province. The plant spread along trade routes to Japan by the 4th century and reached Europe through multiple pathways, including Russian and Dutch traders.

| Characteristic | Allium fistulosum (Welsh Onion) | Allium cepa (Common Onion) | Allium schoenoprasum (Chives) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulb Development | No true bulb; slender white base | Large layered bulb | No bulb; small clustered bulbs |

| Leaf Structure | Hollow, cylindrical, uniform diameter | Flat, solid leaves | Hollow, very thin |

| Growth Habit | Perennial clumping | Annual bulb formation | Perennial grass-like |

| Flavor Profile | Mild, consistent from base to tip | Stronger at base, milder at tips | Delicate, grassy |

| Harvest Season | Year-round in suitable climates | Single annual harvest | Spring through fall |

Optimal Growing Conditions and Practical Cultivation

Allium fistulosum thrives in USDA hardiness zones 3–10, demonstrating remarkable cold tolerance down to -20°F (-29°C). Unlike common onions that require specific day lengths to bulb, Welsh onions grow consistently regardless of photoperiod, making them suitable for diverse geographic locations. They prefer well-drained, loamy soil with pH between 6.0–7.5 and benefit from consistent moisture without waterlogging.

For successful planting, space seeds 1 inch deep and 2 inches apart in rows 12–18 inches apart. Thin seedlings to 4–6 inches apart once they reach 4 inches tall. The plants reach harvest readiness in 60–80 days but can be harvested continuously once established. In colder climates, apply 2–3 inches of mulch before first frost to protect roots for spring regrowth.

Gardeners should note specific context boundaries: Welsh onions struggle in consistently hot climates above 85°F (29°C) where they may bolt prematurely. They also perform poorly in heavy clay soils without amendment. In tropical regions, plant during cooler months for best results. Unlike common onions that require full sun, Welsh onions tolerate partial shade, making them suitable for interplanting in vegetable gardens.

Culinary Applications Across Global Cuisines

The culinary versatility of Allium fistulosum spans numerous world cuisines, each utilizing its unique properties. In East Asian cooking, the entire plant appears in dishes like Japanese negimaki (beef rolls) and Korean pajeon (scallion pancakes). Chinese cuisine features it prominently in stir-fries and as a garnish for noodle soups. The plant's consistent mild flavor allows for using the entire stalk without the sharpness of common onion bases.

Professional chefs value Welsh onions for their cooking stability—they maintain texture better than common scallions when exposed to heat. When substituting in recipes, use a 1:1 ratio for raw applications, but reduce cooking time by 25% compared to regular onions. For maximum flavor extraction, slice diagonally to increase surface area while maintaining structural integrity during cooking.

Nutritional Profile and Health Benefits

Allium fistulosum offers notable nutritional advantages with just 32 calories per 100g serving. It provides 145% of the daily recommended vitamin K, 20% of vitamin C, and significant amounts of vitamin A and folate. The plant contains organosulfur compounds similar to garlic, which research suggests may support cardiovascular health and exhibit antimicrobial properties.

Unlike bulb onions that concentrate beneficial compounds in their outer layers, Welsh onions distribute nutrients evenly throughout the plant. This means you gain nutritional benefits from the entire stalk, not just specific sections. Studies from the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry indicate that cooking methods affect nutrient retention—steaming preserves more vitamin C than boiling, while stir-frying maintains higher levels of organosulfur compounds.

Effective Storage and Preservation Techniques

For short-term storage, keep unwashed Welsh onions in a perforated plastic bag in the refrigerator's crisper drawer for up to three weeks. The ideal storage temperature is 32–36°F (0–2°C) with 95% humidity. For longer preservation, freeze chopped portions in airtight containers after brief blanching—they maintain quality for 6–8 months.

Gardeners harvesting surplus can create living storage by transplanting clumps into containers indoors. Place near a sunny window and water sparingly to maintain growth through winter months. This method provides fresh harvests while preserving the plant's superior flavor compared to frozen alternatives.

Troubleshooting Common Growing Challenges

Yellowing leaves typically indicate nitrogen deficiency—address with compost tea or balanced organic fertilizer. Thrips infestations cause silvery streaks on leaves; control with insecticidal soap sprays every 5–7 days. To prevent onion maggots, rotate planting locations annually and use floating row covers during egg-laying season.

When plants bolt (produce flowers), cut flower stalks immediately to redirect energy to leaf growth. While bolting doesn't harm edibility, it can make leaves slightly tougher. In hot climates, choose heat-tolerant varieties like 'Ishikura' or 'White Lisbon' to minimize premature bolting.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4