Before Tacos and Tomatoes: A Spice-Centric Look at What Native Mexicans Ate Before Colonialism

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What Was the Pre-Colonial Mexican Diet?

- The Spice Bowl of the Ancients

- Maize Magic: The Corn Chronicles

- Beans, Squash, and the Holy Trinity of Agriculture

- Wild Edibles and Forgotten Flavors

- Ancient Cooking Methods That Still Inspire Today

- How Spices Evolved Post-Colonization

- 5 Practical Spice Tips from Ancient Mexico

- Conclusion

Introduction

Ever wondered what your taco-loving ancestors in Mexico were munching on before Europeans showed up with their cows, pigs, and spices from halfway across the world? If you thought churros and cheese were part of the original menu — surprise! They weren't.

In this article, we’ll take a spicy trip down memory lane (or should we say, maize field?) to explore the pre-colonial diet of Native Mexicans. And yes, there will be plenty of spice talk — because long before chili powder hit the supermarket shelves, ancient Mexicans knew how to turn up the heat.

What Was the Pre-Colonial Mexican Diet?

The Native Mexican diet was based around the “Three Sisters” — maize, beans, and squash — along with a variety of local vegetables, fruits, wild game, and naturally occurring spices. There were no refrigerators or supermarkets, but that didn’t stop them from creating bold flavors with what nature provided.

Unlike modern diets that often rely on imported ingredients, pre-colonial food was hyper-local and seasonal. No sugar-laden sodas, no wheat-based breads, and definitely no Parmesan cheese sprinkled on everything. But they had flavor — lots of it!

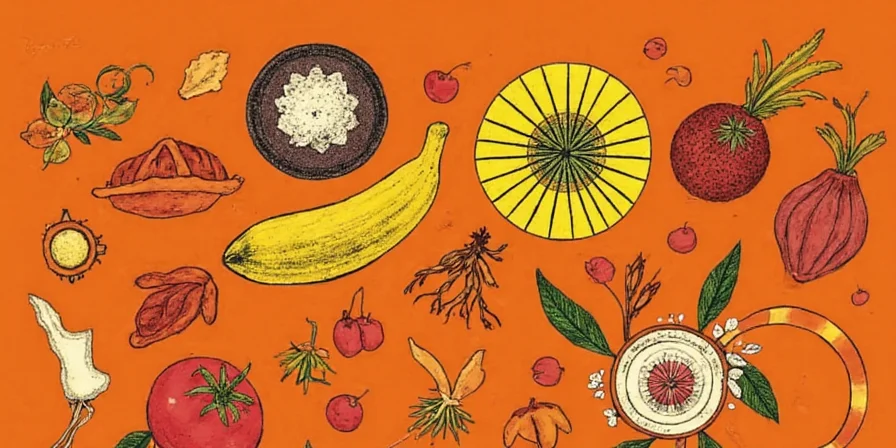

The Spice Bowl of the Ancients

While many associate Mexican cuisine with cumin, black pepper, or garlic — none of these were originally from Mexico. So how did they get so much flavor into their dishes without those common spices?

Ancient Mexicans used a wide array of indigenous plants and seeds to add depth, heat, and aroma to their food. Here’s a breakdown:

| Spice/Herb | Description | Modern Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chilies | Used fresh, dried, or smoked for heat and depth | Core ingredient in salsas, moles, and adobos |

| Cilantro | Natively grown and used as a garnish and flavor booster | Essential in tacos, salads, and salsas |

| Huitlacoche | Edible corn fungus known as “Mexican truffle” | Used in quesadillas and gourmet dishes |

| Epinaca (Papaloquelite) | Strong-flavored herb similar to cilantro | Rarely found outside Mexico, used in traditional stews |

| Vanilla | Originated in Mesoamerica, used in beverages and sweet dishes | Now global, especially in baking and desserts |

Maize Magic: The Nixtamalization Process

Maize (corn) wasn’t just a staple — it was sacred. It formed the base of nearly every meal, from tortillas to tamales to atole (a traditional drink). But it wasn’t simply boiled or grilled. The secret sauce? Nixtamalization.

This process involves soaking and cooking maize in an alkaline solution (like lime water), which removes toxins and enhances nutrient absorption. It also gives tortillas that chewy texture we love today.

Why Maize Was a Game-Changer

- High in carbohydrates and essential amino acids

- Became more digestible after nixtamalization

- Formed the foundation of daily meals across cultures like the Maya, Aztec, and Zapotec

Beans, Squash, and the Holy Trinity of Agriculture

The Three Sisters — maize, beans, and squash — weren’t just dietary staples; they were agricultural companions. Each plant supported the others: maize provided structure for beans to climb, beans fixed nitrogen into the soil, and squash shaded the ground to retain moisture.

Together, they offered a complete protein source and a balanced nutritional profile. Beans added fiber and protein, while squash brought in vitamins and minerals like vitamin A and potassium.

Wild Edibles and Forgotten Flavors

Long before grocery stores stocked kale and quinoa, indigenous communities relied on wild edibles. These included:

- Quelites – edible greens like lamb’s quarters and amaranth leaves

- Pitahaya – wild desert fruit with vibrant color and mild sweetness

- Maguey worms – high-protein insect delicacy still enjoyed today

- Huauzontle – a flowering plant used similarly to broccoli

Ancient Cooking Methods That Still Inspire Today

Without ovens or microwaves, early cooks relied on time-tested techniques that are now trendy again thanks to the farm-to-table movement. Some of the most iconic include:

- Barbacoa – slow-roasting meat underground with hot stones and agave leaves

- Comal grilling – flat griddle used for roasting corn, peppers, and tortillas

- Grinding with metates – stone tools used to crush maize and spices

How Spices Evolved Post-Colonization

When the Spanish arrived, they brought European spices like black pepper, cinnamon, and cumin, which eventually became embedded in Mexican cuisine. While these additions enriched the flavor palette, they also marked a shift away from purely indigenous seasoning practices.

Today, both old and new spices coexist in Mexican kitchens. But understanding the roots of spice use helps us appreciate the ingenuity of pre-colonial culinary traditions.

5 Practical Spice Tips from Ancient Mexico

If you want to channel the spirit of pre-colonial cooking in your kitchen (and let's face it, who doesn't?), here are five spice hacks straight from the ancient playbook:

- Dry roast your chilies first – Enhances flavor and reduces bitterness. Simply toast them on a comal or skillet until fragrant.

- Make your own spice paste with a molcajete – Grinding dried chilies, tomatoes, and herbs together intensifies the flavor.

- Use epazote in beans – This pungent herb adds earthiness and helps reduce bean-induced bloat. Science AND flavor? Yes, please.

- Add huitlacoche for umami – If you can find it frozen or canned, it makes an amazing addition to sauces and fillings.

- Don’t over-season – Let natural flavors shine. A little goes a long way when working with potent ingredients like roasted tomatoes and fresh herbs.

Conclusion

So, next time you bite into a spicy tamale or swirl some mole onto your plate, remember — you're tasting thousands of years of history, culture, and spice mastery. Long before colonizers changed the spice map, Native Mexicans had already built a flavor empire rooted in the land, the seasons, and the sacred art of cooking.

Whether you're a professional chef or just someone who loves a good green salsa, there’s something deeply satisfying about going back to the roots. Embrace the Three Sisters, play with native herbs, and don’t forget — sometimes the best spices aren’t even spices in the traditional sense.

You might not have access to a molcajete or a pit oven, but you can still honor the spirit of pre-colonial spice traditions — one flavorful bite at a time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4